Thus, the hallmark of the Song of Ice and Fire for many fans, supposedly never knowing when another major character will be killed off. This is actually less true than many believe it to be, in the same way that Arya's assertion that "anyone" can be killed is true only so far as one is capable of doing so. Or having the friends to do so.

This episode was rife with excellent character moments and exchanges between the different players. All of the performers seemed to be on their game. One wonders if the direction had any part of it or whether everyone was just given plenty of red meat to toy with in this script. While it lacked some of the powerful one-liners of previous episodes, it exceeded them in story and performance and was the best episode of the season so far; at least for those of us that appreciate the sometimes-dizzying complexity of the story.

I found myself wondering if the shadow scene was too abrupt, in that it is a major turning point of the book. Of course, I kind of felt that about the book, as well, as I remember questioning whether Renly was actually dead and what, in fact, had killed him until I arrived at the next Brienne/Catelyn scene and everything coalesced. Of course, this episode was so packed with people and events and their reactions that one wonders whether it could have been anything but abrupt. For the first time, I wondered whether non-reading viewers were going to have trouble following what was happening, as new characters like Qhorin Halfhand were introduced without much direct indication, and important events were taking place at a pace that may not have allowed the new viewer much time to digest and by which to appreciate their magnitude. That said, I thought the overall pacing felt much less rushed than other episodes this season.

When Littlefinger arrived at the Baratheon/Tyrell camp last episode in a deviation from the books, I thought the producers were doing so in order to make the machinations of Tyrion and Petyr more obvious, since much of that happens off-camera in the books. In a way, it could be seen as ham-handed. But I think it worked well here, especially with Aidan Gillen playing the canny negotiator with an emotional Loras being reminded, as Brienne was, that revenge is difficult when you're dead.

The character development moments were plentiful and almost all were both subtle and involving more than one person coming to a new moment. Davos and Stannis arguing over Melisandre; Tyrion and Cersei continuing Dinklage and Headey's remarkable chemistry; Theon realizing the opportunity for true betrayal and potential glory with Dagmer Cleftjaw; Arya and Jaqen H'ghar striking their deal; Bronn, Tyrion, and one of the Wisdoms of the Alchemists' Guild arguing over the wildfire (with the unintentionally ironic statement "Men win wars, not magic tricks." coming shortly after Renly's assassination); Bran and Ser Rodrik; Xaro Xhoan Daxos and Daenerys; all of these were great scenes that gave real insight into the characters involved and demonstrated the skill of the people playing them.

It was good to see that some of the best material in the book and probably the most intriguing relationship (Arya and Jaqen) was given plenty of screen time. This encounter, more than anything else, sets Arya on her presumed life path and gives her the realization that she can genuinely alter her life and the expectations around her by the force of her own will. Maisie Williams continues to be an absolute treasure as her willful but subservient reaction to Tywin's interrogation wins her his grudging respect and her reaction to the Tickler's death was, by far, the best moment of the episode and, fittingly, the climax.

Short bits:

I thought the detail of Tyrion not wearing the badge of the Hand in the increasingly unhappy streets of Kings Landing was smart. While he and Bronn are obvious to us, they're less likely to be noticed by the smallfolk on the streets.

Although I enjoyed the moment with Theon and Dagmer, the routine of Theon getting treated like an alien is getting a little old. If they're truly moving the story at an accelerated pace, we could probably live without yet another scene of Yara rubbing Theon's nose in the shit that his life has seemingly become.

Dolorous Edd was in fine form: "We'll live another day. Hurrah."

I'm really unsure about the seeming jealousy and cultural conflict between Doreah and Irri. I don't know that the personal conflict serves a whole lot of purpose and the spotlight on the Dothraki being strangers in a strange land was better emphasized by two of them bickering over how to dismantle a golden statue before they leave. Was it really necessary to have the two handmaidens arguing over whether Daenerys is a princess or a khaleesi?

In that same vein: "Valyrian stone"? Really? What's next? Valyrian wood? Valyrian grass, the kind you just can't get out of the crevices in your driveway? I was fine with Valyrian steel. It's a fantasy trope, like mithril and adamantium, but it's based in the history of Damascus steel and provides a nice link to the past in the hereditary swords. Couldn't they have just said that Xaro's vault door was solid granite or 'black quartz' if you really want to invoke the Mohs scale?

On the other hand, I'm glad that they laid a little groundwork for Pyatt Pree. The House of the Undying sequence in the book was not one of my favorites. It felt like going from the "realistic" fantasy of Game of Thrones right into the introspective, New Wave science fiction of the late 60s and early 70s. I'm really wondering both how they're going to handle that scene and what the audience reaction will be like.

Monday, April 30, 2012

Wednesday, April 25, 2012

Directors: He's all out of bubblegum

So, I thought I'd post a bit about some of my favorite directors. There are a couple that have made lasting impressions with a very wide audience over a long period (Akira Kurosawa, Stanley Kubrick), a couple that have become prominent in recent years and have made big splashes (David Fincher, Christopher Nolan), and a couple that I regard as brilliant at an early point in their careers, only to fade to obscurity (John Carpenter) or seemingly resign themselves to Hollywood spectacle (Ridley Scott.) When I write these, I'm going to skip around a bit to cover the films that I think define the director or that resonate the most with me or that perhaps represent a defining moment, either within the scope of the director's normal approach, or as a marked contrast to it. This time I'm thinking about Carpenter.

John Carpenter is one of those directors whose style is often immediately apparent when his films begin. For his first several films, his approach didn't vary overmuch and it worked well for most of the stories that he was trying to tell. It was that style that attracted me to his work and the one I most missed as he moved on to other things. Granted, not everything can be approached with the same Steadicam usage that Carpenter made standard for the horror genre. But, like any actor, it's possible that people will only see you as a "horror director" and, thus, that's all you'll get offered. Carpenter would admit in his later years that many of his lesser productions were the result of being offered nothing else and having to make a living, as it were.

In the horror genre, few faces (well, masks, actually) are as iconic as that of Michael Myers, the implacable killer of Halloween (1978), Carpenter's first big success. While he had started his career several years before and had become a bit of a hero in Hollywood for his film, Dark Star, which has decent production values for a science fiction film produced on a budget of only $60,000, he was still stuck multi-tasking on independent productions in 1978 when Halloween hit the theaters. He directed, co-produced, co-wrote, and scored the film, making it one among his filmography that really resonates with his vision and approach from beginning to end. Halloween emphasized elements that would later become the trademarks of his better films: eerie atmospheres (whether horror or not), wide perspectives, steady and lasting shots, often ambiguous endings, and highly memorable music:

Despite the schlocky set elements (gravestone in the bed alongside the conveniently-lit jack-o'-lantern) and the cheap scares (dead boyfriend swinging into the shot from the closet), there are great moments in that scene: the long take on Laurie as she wails over the death of her friend; the appearance of Michael's face as she steps away from the bedroom and he attacks; his implacable advance down the stairs.) These are all elements that would be often missed in the widespread imitations of Halloween that followed and which created the modern slasher genre. And following it all is the ominous and eerie music, composed by Carpenter. The scene would be severely hampered without it and it's to his credit that he understood where to shift tones and keys to emphasize what was happening on screen. I'm not much of a horror fan and even less of a slasher fan, but Halloween is a great example of Carpenter's grasp of story and pacing.

What followed was one of the greatest cult movies ever made: Escape from New York (1981.)

That poster always amuses me because, in the film, Liberty Island is actually the police headquarters for the prison that Manhattan Island has become and the statue is seen standing, in perfect condition, several times. But I suppose marketers were trying to tap into the Planet of the Apes sensation.

I'm a sucker for post-apocalyptic storylines and Escape plays right into that. Carpenter's tendencies (long shots, spooky atmospheres) are on full display in this sci-fi thriller and he uses a capable supporting cast (Lee Van Cleef, Ernest Borgnine, Adrienne Barbeau) very well alongside his lead, Kurt Russell and, of course, the once-again scintillating score. He originally wrote the screenplay right after Watergate, which explains the heavily cynical attitude toward the office of president and other institutions but, given that the Cold War was still in full flower when Escape was released, it remains firmly enmeshed with the zeitgeist of the times. One quiet scene is particularly notable:

Carpenter doesn't spend too much time on dialogue exchanges in his films, as the action is usually moving faster than exposition would allow for. But there are elements that are key to this plot that need to be sorted out. It also provides a great moment for one of the Western heroes of yesteryear (Van Cleef) to square off with Russell, who was attempting to change his film image to that of action hero (and largely succeeded.) Even in an exchange scene, we can see Carpenter's love for the long shot, as Plissken presents his cuffs for release, and the love for the wide shot, as even while we're looking for Plissken's reactions to Hauk's offer, we stay pulled back from where the former is sitting. I was chagrined to see this Youtube clip end where it did because the next line from Plissken is "Why me?" Hauk's response: "You flew the Gullfire over Leningrad. You know how to get in quiet. You're all I've got."

It was that line, in addition to the commentary about special forces teams ("Black Flag", "Texas Thunder") that later inspired William Gibson to create a major plot element in Neuromancer, the foundation novel of the cyberpunk movement. As Gibson stated: "It turns out to be just a throwaway line, but for a moment it worked like the best SF where a casual reference can imply a lot." Armitage, a major character in the novel, has flashbacks at one point about his special forces unit, Omaha Thunder, running into trouble as they attempted a cyber-assault on the Soviet network (something that, incidentally, is a major element of international competition and espionage today, although less flamboyantly.) These little details are emblematic of Carpenter scripts and visuals and appear frequently in his best films. They're indicative of a director in command of his story and all the little aspects that make up the big picture.

With the major critical and commercial success of those two films, Carpenter had hit his stride and now moved on to a remake of a classic 1950s-era science fiction film: The Thing (1982.)

The Thing holds a special place in Carpenter's career, because it's the scene of what is possibly his greatest triumph and his greatest failure. The Thing has been hailed in the past two decades as one of the greatest horror films ever made but, at the time, it was criticized for being "excessive" and was vastly overshadowed at the time of its release by E. T.: The Extra-Terrestrial. Thus, it ended up being a commercial failure, as the audiences of the time seemed eager for sentimental pap, as opposed to being scared out of the theater (which, admittedly, is not an entirely illogical choice.)

All of Carpenter's usual tendencies are here, but he hired Ennio Morricone (of Man with No Name trilogy fame) to score the film; later replacing some of Morricone's orchestral work with his customary keyboards. The result was not a bad score, but certainly one that was less memorable and less instantly recognizable to fans (and many non-fans) than either the Halloween or Escape themes. Did that have an impact on the film's reception? Perhaps. This was also Carpenter's first film with a truly appropriate budget which, of course, set him up for genuine failure when the film failed to find an audience (The Fog, a film produced in 1980 had decent returns, while Escape returned 7:1 on a $6 million budget and Halloween returned $51 million on a budget of $325,000, making it one of the most successful independent films ever made.)

While Carpenter's film was more faithful to the original John W. Campbell story, Who Goes There?, than Howard Hawks' The Thing From Another World (1951) (Pedantic film titles, FTW!), I think there is validity to some of the criticism about too much emphasis on the phenomenal special effects. There was more attention paid to rubbery creatures than to pacing and atmosphere. Again, a consequence of having more money to play with? Maybe. When you can hire people to do tasks that you once did with the fire of an aspiring filmmaker and throw money at problems that you used to have to invent your way out of, does that degrade the end result?

A great example of that change in approach is in this famous scene, when the creature attacks the dog teams at the base and the crew gets its first real close encounter:

In films like Halloween, the creature would have attacked the dogs off-screen and the noise of their dismay would have alerted the rest of the crew, and not just MacReady. The only visible evidence of the creature would have been right before half of it escaped and the rest was burned. I think the suspense that was built later in the film, as paranoia grew amongst the crew, was just as effective for the story he was trying to tell here. But the opportunity to maintain the suspense of mystery was lost in order to demonstrate the basic weirdness of the creature's shapeshifting ability. It's trending more toward shock value and away from the stylistic approach he had used earlier. Again, it can be just as effective. I'm just not sure that was the case here. All that said, The Thing remains an excellent film and a continuing example of the skill of its director.

The financial failure of The Thing began to affect the kind of scripts that Carpenter was offered. He managed to sign on to Starman (1984) (which had, coincidentally, been chosen by Columbia Pictures over E. T.) and, again, changed his approach and style to a more "mainstream" shoot, as it were, to present what he perceived as a romantic comedy but which actually ran a bit deeper than that and which many critics regarded as one of the best films of 1984; earning an Oscar nomination for Jeff Bridges in the lead. The difference in shot length can be seen in this exchange between Bridges and Karen Allen in a still poignant and well-played scene:

This scene lacks the longer pauses on the speaker which allow the audience to register the play of emotion and allow the actor to fill the scene a bit, as in the conversation between Hauk and Plissken above. It's a subtle difference, but it's an atmosphere changer from what seemed to be Carpenter's intent to add weight to certain frames of dialogue and toward a shoot that requires the actor to carry it alone. Starman was critically hailed but only a modest success at the box office.

Following this was a film that engenders a broad spectrum of reaction from moviegoers and critics: Big Trouble in Little China (1986.)

Point blank, Big Trouble is an awful film. Unless viewed deliberately as a parody (which is certainly possible, although Carpenter has never declared it to be such), it barely approaches the level of B-movie. The script is clunky and linear. The acting is sophomoric. The effects are cheap and obvious. The original script was massively rewritten and the film was rushed into production to emerge before the Eddie Murphy vehicle, The Golden Child, and that sloppy development process shows in every corner and chop-socky scene of this film. Some critics found it "fun", but most found it as horrible as I did. It has, like Escape, became a huge cult hit in later years. Carpenter has said that he took the project to fulfill a dream of doing a martial arts movie but was also relatively indignant about the film's failure at the box office, saying that the studio didn't support it effectively. At that point, he decided that life as a major studio director was no longer for him and he declared that he would only do independent films from then on.

Unfortunately, most of those independent films have been bombs. From more Halloween sequels, to Memoirs of an Invisible Man to Vampires to Ghosts of Mars, none of them have really been either interesting stories on the order of Escape or interesting technique on the order of Halloween. The one exception was yet another film that has become a cult classic, know as They Live (1988):

Based on both fictional sources and Carpenter's own growing distaste for the commercialization of society, They Live is halfway between a spoof and a serious science fiction drama. Hyperkinetic in the same manner as Big Trouble, it also tries to deliver a serious message about the danger of a somnolent populace and the influence of the wealthy in a very Fitzgeraldian way: the rich are really different from you and me... because they're aliens and they're still screwing us in plain sight. Carpenter had, by this time, largely discarded his attempts to build atmosphere in exchange for raw message and delivery by the actor. His unusual choice for the lead in They Live was the professional wrestler, Roddy Piper, who did a capable job, given that his role was essentially to be a ham (this is where the film arcs toward spoof) so as to attract as much attention as possible in order to get people to listen to his warnings. In this well-played scene, Carpenter establishes the threat while still maintaining the aura of camp and incredulity about it all that prevents the film from becoming a Body Snatchers-level horror film:

Of course, given his earlier track record, the film might have worked better if he had veered more toward the darker aspect of the overall threat, but those days seemed to be behind him.

Whenever I talk about favorite directors of mine, I usually bring up "early John Carpenter." That's typically code for Halloween, Escape from New York, and The Thing. I think the early part of his career was a time when he genuinely brought something to Hollywood in terms of style and approach. Frustration with the material he was being offered and his general disdain for the Hollywood system led him to bury himself in independent projects that didn't end up in the major studios because they were, by and large, awful, which is a tremendous shame for someone who was clearly so talented and innovative at the beginning of his career. In the same way that big stars are sometimes rehabilitated with modern, weighty material (think Burt Reynolds in Boogie Nights), I keep hoping that one of these days someone will offer Carpenter a project that sings to his abilities and sense of style and we'll get something moody and eerie and worthwhile that will put his legacy on a firmer foundation.

John Carpenter is one of those directors whose style is often immediately apparent when his films begin. For his first several films, his approach didn't vary overmuch and it worked well for most of the stories that he was trying to tell. It was that style that attracted me to his work and the one I most missed as he moved on to other things. Granted, not everything can be approached with the same Steadicam usage that Carpenter made standard for the horror genre. But, like any actor, it's possible that people will only see you as a "horror director" and, thus, that's all you'll get offered. Carpenter would admit in his later years that many of his lesser productions were the result of being offered nothing else and having to make a living, as it were.

In the horror genre, few faces (well, masks, actually) are as iconic as that of Michael Myers, the implacable killer of Halloween (1978), Carpenter's first big success. While he had started his career several years before and had become a bit of a hero in Hollywood for his film, Dark Star, which has decent production values for a science fiction film produced on a budget of only $60,000, he was still stuck multi-tasking on independent productions in 1978 when Halloween hit the theaters. He directed, co-produced, co-wrote, and scored the film, making it one among his filmography that really resonates with his vision and approach from beginning to end. Halloween emphasized elements that would later become the trademarks of his better films: eerie atmospheres (whether horror or not), wide perspectives, steady and lasting shots, often ambiguous endings, and highly memorable music:

Despite the schlocky set elements (gravestone in the bed alongside the conveniently-lit jack-o'-lantern) and the cheap scares (dead boyfriend swinging into the shot from the closet), there are great moments in that scene: the long take on Laurie as she wails over the death of her friend; the appearance of Michael's face as she steps away from the bedroom and he attacks; his implacable advance down the stairs.) These are all elements that would be often missed in the widespread imitations of Halloween that followed and which created the modern slasher genre. And following it all is the ominous and eerie music, composed by Carpenter. The scene would be severely hampered without it and it's to his credit that he understood where to shift tones and keys to emphasize what was happening on screen. I'm not much of a horror fan and even less of a slasher fan, but Halloween is a great example of Carpenter's grasp of story and pacing.

What followed was one of the greatest cult movies ever made: Escape from New York (1981.)

That poster always amuses me because, in the film, Liberty Island is actually the police headquarters for the prison that Manhattan Island has become and the statue is seen standing, in perfect condition, several times. But I suppose marketers were trying to tap into the Planet of the Apes sensation.

I'm a sucker for post-apocalyptic storylines and Escape plays right into that. Carpenter's tendencies (long shots, spooky atmospheres) are on full display in this sci-fi thriller and he uses a capable supporting cast (Lee Van Cleef, Ernest Borgnine, Adrienne Barbeau) very well alongside his lead, Kurt Russell and, of course, the once-again scintillating score. He originally wrote the screenplay right after Watergate, which explains the heavily cynical attitude toward the office of president and other institutions but, given that the Cold War was still in full flower when Escape was released, it remains firmly enmeshed with the zeitgeist of the times. One quiet scene is particularly notable:

Carpenter doesn't spend too much time on dialogue exchanges in his films, as the action is usually moving faster than exposition would allow for. But there are elements that are key to this plot that need to be sorted out. It also provides a great moment for one of the Western heroes of yesteryear (Van Cleef) to square off with Russell, who was attempting to change his film image to that of action hero (and largely succeeded.) Even in an exchange scene, we can see Carpenter's love for the long shot, as Plissken presents his cuffs for release, and the love for the wide shot, as even while we're looking for Plissken's reactions to Hauk's offer, we stay pulled back from where the former is sitting. I was chagrined to see this Youtube clip end where it did because the next line from Plissken is "Why me?" Hauk's response: "You flew the Gullfire over Leningrad. You know how to get in quiet. You're all I've got."

It was that line, in addition to the commentary about special forces teams ("Black Flag", "Texas Thunder") that later inspired William Gibson to create a major plot element in Neuromancer, the foundation novel of the cyberpunk movement. As Gibson stated: "It turns out to be just a throwaway line, but for a moment it worked like the best SF where a casual reference can imply a lot." Armitage, a major character in the novel, has flashbacks at one point about his special forces unit, Omaha Thunder, running into trouble as they attempted a cyber-assault on the Soviet network (something that, incidentally, is a major element of international competition and espionage today, although less flamboyantly.) These little details are emblematic of Carpenter scripts and visuals and appear frequently in his best films. They're indicative of a director in command of his story and all the little aspects that make up the big picture.

With the major critical and commercial success of those two films, Carpenter had hit his stride and now moved on to a remake of a classic 1950s-era science fiction film: The Thing (1982.)

The Thing holds a special place in Carpenter's career, because it's the scene of what is possibly his greatest triumph and his greatest failure. The Thing has been hailed in the past two decades as one of the greatest horror films ever made but, at the time, it was criticized for being "excessive" and was vastly overshadowed at the time of its release by E. T.: The Extra-Terrestrial. Thus, it ended up being a commercial failure, as the audiences of the time seemed eager for sentimental pap, as opposed to being scared out of the theater (which, admittedly, is not an entirely illogical choice.)

All of Carpenter's usual tendencies are here, but he hired Ennio Morricone (of Man with No Name trilogy fame) to score the film; later replacing some of Morricone's orchestral work with his customary keyboards. The result was not a bad score, but certainly one that was less memorable and less instantly recognizable to fans (and many non-fans) than either the Halloween or Escape themes. Did that have an impact on the film's reception? Perhaps. This was also Carpenter's first film with a truly appropriate budget which, of course, set him up for genuine failure when the film failed to find an audience (The Fog, a film produced in 1980 had decent returns, while Escape returned 7:1 on a $6 million budget and Halloween returned $51 million on a budget of $325,000, making it one of the most successful independent films ever made.)

While Carpenter's film was more faithful to the original John W. Campbell story, Who Goes There?, than Howard Hawks' The Thing From Another World (1951) (Pedantic film titles, FTW!), I think there is validity to some of the criticism about too much emphasis on the phenomenal special effects. There was more attention paid to rubbery creatures than to pacing and atmosphere. Again, a consequence of having more money to play with? Maybe. When you can hire people to do tasks that you once did with the fire of an aspiring filmmaker and throw money at problems that you used to have to invent your way out of, does that degrade the end result?

A great example of that change in approach is in this famous scene, when the creature attacks the dog teams at the base and the crew gets its first real close encounter:

In films like Halloween, the creature would have attacked the dogs off-screen and the noise of their dismay would have alerted the rest of the crew, and not just MacReady. The only visible evidence of the creature would have been right before half of it escaped and the rest was burned. I think the suspense that was built later in the film, as paranoia grew amongst the crew, was just as effective for the story he was trying to tell here. But the opportunity to maintain the suspense of mystery was lost in order to demonstrate the basic weirdness of the creature's shapeshifting ability. It's trending more toward shock value and away from the stylistic approach he had used earlier. Again, it can be just as effective. I'm just not sure that was the case here. All that said, The Thing remains an excellent film and a continuing example of the skill of its director.

The financial failure of The Thing began to affect the kind of scripts that Carpenter was offered. He managed to sign on to Starman (1984) (which had, coincidentally, been chosen by Columbia Pictures over E. T.) and, again, changed his approach and style to a more "mainstream" shoot, as it were, to present what he perceived as a romantic comedy but which actually ran a bit deeper than that and which many critics regarded as one of the best films of 1984; earning an Oscar nomination for Jeff Bridges in the lead. The difference in shot length can be seen in this exchange between Bridges and Karen Allen in a still poignant and well-played scene:

This scene lacks the longer pauses on the speaker which allow the audience to register the play of emotion and allow the actor to fill the scene a bit, as in the conversation between Hauk and Plissken above. It's a subtle difference, but it's an atmosphere changer from what seemed to be Carpenter's intent to add weight to certain frames of dialogue and toward a shoot that requires the actor to carry it alone. Starman was critically hailed but only a modest success at the box office.

Following this was a film that engenders a broad spectrum of reaction from moviegoers and critics: Big Trouble in Little China (1986.)

Point blank, Big Trouble is an awful film. Unless viewed deliberately as a parody (which is certainly possible, although Carpenter has never declared it to be such), it barely approaches the level of B-movie. The script is clunky and linear. The acting is sophomoric. The effects are cheap and obvious. The original script was massively rewritten and the film was rushed into production to emerge before the Eddie Murphy vehicle, The Golden Child, and that sloppy development process shows in every corner and chop-socky scene of this film. Some critics found it "fun", but most found it as horrible as I did. It has, like Escape, became a huge cult hit in later years. Carpenter has said that he took the project to fulfill a dream of doing a martial arts movie but was also relatively indignant about the film's failure at the box office, saying that the studio didn't support it effectively. At that point, he decided that life as a major studio director was no longer for him and he declared that he would only do independent films from then on.

Unfortunately, most of those independent films have been bombs. From more Halloween sequels, to Memoirs of an Invisible Man to Vampires to Ghosts of Mars, none of them have really been either interesting stories on the order of Escape or interesting technique on the order of Halloween. The one exception was yet another film that has become a cult classic, know as They Live (1988):

Based on both fictional sources and Carpenter's own growing distaste for the commercialization of society, They Live is halfway between a spoof and a serious science fiction drama. Hyperkinetic in the same manner as Big Trouble, it also tries to deliver a serious message about the danger of a somnolent populace and the influence of the wealthy in a very Fitzgeraldian way: the rich are really different from you and me... because they're aliens and they're still screwing us in plain sight. Carpenter had, by this time, largely discarded his attempts to build atmosphere in exchange for raw message and delivery by the actor. His unusual choice for the lead in They Live was the professional wrestler, Roddy Piper, who did a capable job, given that his role was essentially to be a ham (this is where the film arcs toward spoof) so as to attract as much attention as possible in order to get people to listen to his warnings. In this well-played scene, Carpenter establishes the threat while still maintaining the aura of camp and incredulity about it all that prevents the film from becoming a Body Snatchers-level horror film:

Of course, given his earlier track record, the film might have worked better if he had veered more toward the darker aspect of the overall threat, but those days seemed to be behind him.

Whenever I talk about favorite directors of mine, I usually bring up "early John Carpenter." That's typically code for Halloween, Escape from New York, and The Thing. I think the early part of his career was a time when he genuinely brought something to Hollywood in terms of style and approach. Frustration with the material he was being offered and his general disdain for the Hollywood system led him to bury himself in independent projects that didn't end up in the major studios because they were, by and large, awful, which is a tremendous shame for someone who was clearly so talented and innovative at the beginning of his career. In the same way that big stars are sometimes rehabilitated with modern, weighty material (think Burt Reynolds in Boogie Nights), I keep hoping that one of these days someone will offer Carpenter a project that sings to his abilities and sense of style and we'll get something moody and eerie and worthwhile that will put his legacy on a firmer foundation.

Tuesday, April 24, 2012

Pride and fall

That's Marcus, of course. It's Meditations XII, 27, and specifically about pride. The first passage there is essentially a restatement of the old "Let every action aim solely for the common good." It's a reminder that virtuous actions for the benefit of others will make a person happy (or, at least make a Stoic happy) while self-directed actions will, in the long run, make us unhappy. Pride is part of that because many self-directed actions are driven by pride. Wanting to succeed, wanting to achieve, wanting to display, wanting to be seen or known or revered or admired; all forms of pride. That's something that I've been struggling with for most of my life.Constantly bring to your recollection those who have complained greatly about anything, those who have been most conspicuous by the greatest fame or misfortunes or enmities or fortunes of any kind: then think where are they all now? Smoke and ash and a tale, or not even a tale. And let there be present to your mind also everything of this sort, immense how Fabius Catullinus lived in the country, and Lucius Lupus in his gardens, and Stertinius at Baiae, and Tiberius at Capreae and Velius Rufus (or Rufus at Velia); and in fine think of the eager pursuit of anything conjoined with pride; and how worthless everything is after which men and women violently strain; and how much more philosophical it is in the opportunities presented to you to show yourself just, temperate, obedient to the gods, and to do this with all simplicity: for the pride which is proud of its want of pride is the most intolerable of all.

As I've noted before, for all my supposed intelligence, my accomplishments are relatively few and far-between. For all of my pride in my ability to comprehend and utilize information, I haven't turned that into any kind of sustained success. I'm not talking solely about material success, although that would be nice. If I could find my way to a regular writing gig that I could make a career out of, that'd be great. I could make a living doing something that I enjoy and that at least a few people have suggested I have a certain amount of talent for and that they enjoy. But I found that I had just as much pride in accomplishing something that served more people than just me and in more than simply entertainment, in true Stoic fashion. I took pride in those virtuous actions for the public weal. Is that counter-intuitive for the Stoic? Somewhat. After all, that last line about acting with simplicity and false modesty being the worst sort of pride is directed primarily at those who would hold themselves up to be respected for their virtue.

Of course, part of my struggle has always been from another well-known quote of Marcus': "Man is worth as much as what he is interested in is worth." - Meditations VII, 3. If one is interested in the more virtuous of ideals in one's society, is that not a form of pride? Those things are worth more, therefore said person is worth more. Is that the measure of it or a faulty interpretation? Is it appropriate to use pride to drive oneself to be more active and more successful in those idealistic pursuits, knowing that one is not only serving the community but also making himself "worth" more? It seems to become wrong to want to be worth more. It should instead be left up to society to measure that worth and then, perhaps, take equal doses of pride and humility in the fact that one has achieved "greater worth". Of course, given the idiotically skewed values of our current society, expecting that one's worth will be properly measured is a mortgage-backed security of a rather profound quality. Or is it simply my failing as a Stoic that I would perhaps enjoy writing about films more than I would organizing another progressive campaign?

And if one's worth really is greater from this expression of selflessness, does it make sense that the most self-directed action of all- suicide -becomes even more of a crime of self-indulgence for depriving society of that supposed worth? That sounds an awful lot like an expression of extreme pride. One engages in that ultimate self-directed act and presumes that people will feel loss because of one's supposed virtue (this is putting aside emotional attachments, of course; this is part of why Stoics are often perceived as 'unemotional'), so that is properly perceived as an expression of pride (and, unlike the standard Stoic belief, one won't be unhappy after that's over...) But pride in the loss or pride in the action?

For that matter, if one isn't contributing anything useful to society at this point, then there is no virtue to deny said society except for unknown potential. So, suicide deprives no one except the actor of anything. It remains a very self-directed act and not directly beneficial to society, but not implicitly harmful, either. And, of course, classical Stoicism (outside of Marcus) tends to speak on this repeatedly, in that once a person recognizes that a "naturally flourishing" life is unattainable, suicide becomes justifiable with no harm to one's inherent virtue. Seneca, for example, spoke frequently about "living well", as opposed to "mere living" and suggested that a wise person "lives as long as he ought, not as long as he can." Marcus, no different, said essentially the same thing:

The question then becomes: Why is that naturally flourishing life unattainable and is it a failure of self or simply an expression of fate? "Every event happens in such a way that your nature can either support it or cannot." X, 3. " "Either you go on living in the world and are familiar with it by now, or you go out, and that by your own will, or else you die and your service is accomplished. There is nothing beside these three; therefore be of good courage." X, 22.When you have assumed these names, good, modest, true, rational, a person of equanimity, and magnanimous, take care that you do not change these names; and if you should lose them, quickly return to them. And remember that the term Rational was intended to signify a discriminating attention to every single detail and to do so with due diligence; and that Equanimity is the voluntary acceptance of the things which are assigned to you by the common nature; and that Magnanimity is the elevation of the intelligent part above the pleasurable or painful sensations of the flesh, and above that poor thing called fame, and death, and all such things. If, then, you maintain yourself in the possession of these names, without desiring to be called by these names by others, you will be another person and will enter on another life. For to continue to be such as you have hitherto been, and to be torn in pieces and defiled in such a life, is the character of a very stupid person and one overfond of life, and like those half-devoured fighters with wild beasts, who though covered with wounds and gore, still plead to be kept to the following day, though they will be exposed in the same state to the same claws and bites. Therefore fix yourself in the possession of these few names: and if you are able to abide in them, abide as if you were removed to certain islands of the Happy. But if you shall perceive that you fall out of them and do not maintain your hold, go courageously into some nook where you shall maintain them, or even depart at once from life, not in passion, but with simplicity and freedom and modesty, after doing this one laudable thing at least in your life, to have gone out of it thus. In order, however, to the remembrance of these names, it will greatly help you, if you remember the gods, and that they wish not to be flattered, but wish all reasonable beings to be made like themselves; and if you remember that what does the work of a fig-tree is a fig-tree, and that what does the work of a dog is a dog, and that what does the work of a bee is a bee, and that what does the work of a human being is a human being.

Monday, April 23, 2012

"Bronn, the next time Ser Meryn speaks, kill him."

Thus, the line of the night in an up-and-down episode of GoT; delivered, as usual, by Tyrion, who has all the best lines in the book, too (at least until Dance of Dragons, where Jon steals what may be the line of the series, to date.) That's replicating a pattern, but other elements of this episode are quite new. One of the most notable, of course, was the introduction of Harrenhal and Qarth in the opening credits. However, I also noticed that even though Pyke, Winterfell, and The Wall were all shown, there was no action in any of those sites. The credit locations haven't always exactly matched the episode's scenes, but that's the largest departure that I can recall. Furthermore, since in the books, Renly had moved to Storm's End to confront Stannis' siege, would it have been so difficult to identify Storm's End as where Renly's camp had been hanging out, rather than on some unknowable part of the coastline? What follows is dark and full of spoilers...

I feel like there's a bit of preachiness seeping into the script here (and, admittedly, it could be frustration from a very disappointing Mad Men episode spilling over the banks) but it's clear that a motivation for many of the women in the storyline has become "Why must everyone be fighting?" It's as good a question to ask as any, of course, but the story has already presented sufficient cause for at least some combat to be taking place (the Mountain riding rampant across the Riverlands, Joffrey being Aerys, Jr., Stannis basically starting a religious war), so it's kind of a specious one. But, since the question has been asked, the show proceeds to reinforce the whys even moreso than before with a couple scenes that are bordering on the gratuitous: Joffrey mistreating Tyrion's gift and the Harrenhal torture scene. Certainly, there's nothing wrong with continuing to point out what a sociopath Joffrey is (played excellently by Jack Gleeson, who gives a sincere sigh of pleasure when one whore starts abusing the other) but after the throne room scene with Sansa, was it necessary to see another woman get the scepter treatment? And, of course, some evidence of what's happening at Harrenhal is important to Arya's story and to the possible introduction of Vargo Hoat and the Brave Companions (in addition to bringing about mention of the Brotherhood without Banners), but it just seemed to stretch it a bit far when we were re-entering the scene and spent a few seconds watching someone's head get hammered onto a stake. Yes, yes, the horrors of war. We get it. You do remember you only have 10 episodes to fit in over 1000 pages of story, yes?

Adding to the preachiness is the introduction of Jeyne Westerling (played by the lovely Oona Chaplin, granddaughter of the great Charlie and namesake of his wife) who claims to be from Volantis (odd and partially pointless, if true, as the Westerlings are bannermen to the Lannisters, providing some of the poignancy of her relationship with the King of the North) and who implicitly blames Robb for responding to the new Mad King in the same way his father did. Yes, it would be great if all problems could be solved by negotiation and passive resistance. It'd be especially great since the common people are the ones who suffer most in any war, not the lords/Congressmen who start it which is, indeed, one of the overarching themes of Martin's work. But this point is being driven home in the same way everything looks like a nail if all you have is a hammer. Surely introducing Jeyne as someone helping the wounded is as poignant a reminder of how devastating the war is as making her blame Robb for the entirety of it? Given that the Lannisters took the field first and unleashed the Mountain before Robb ever thought of leaving Winterfell, methinks the frustration is slightly misplaced. Of course, there's no way Jeyne would know that but the aggression which soon turns to romance bit makes their relationship more than a bit Hollywood for my taste.

Bringing this all back around to the other among the host of strong, female characters in the show, we find Daenerys, four episodes in, finally walking through the gates of Qarth. Xaro Xhoan Daxos looks absolutely nothing like I had imagined him, which is unusual for the show so far. Almost everyone else has at least been an approximation. Nonso Anozie looks too big and too normal. And he's missing the jewels in his nose. But that's not a huge problem. What bugged me even more was the first appearance of Roose Bolton without even a hint of eeriness to the man. Seriously, does this

look like the lord of the Dreadfort or does this? (Bottom left is Roose Bolton.) Again, it's not a disaster and certainly Bolton's seeming normalcy in public and... deviations in private are part of what make him who he is. But I think they missed a moment of one kind to introduce him. Of course, you can make a moment of another kind later by showing the true nature of this unassuming man who only talks about flaying people...

I know. Bitch, bitch, bitch. You'd think I hate the show. Tyrion's scenes were, once again, brilliant, as Dinklage continues to play the role of a man with a firm grasp of the rest of the world's short hairs to the hilt. But I hope the preachiness slowly leaches (no, leeches are Bolton's friends) out of the scripts as we proceed. I realize that's impossible for Catelyn's character, but every other woman doesn't have to be reproving all the time.

Thursday, April 19, 2012

On Westerns

Sometime last year I made an off-hand comment about doing a post on Westerns, as they've long been one of the more interesting genres of American film, in my opinion. I grew up in the 70s, when the Western was largely dormant, but Clint Eastwood's famous "Man with No Name" trilogy was present in syndication and he and Lee Van Cleef became early heroes of mine (alongside Mr. Spock, Godzilla, and Cornelius from Planet of the Apes.) I think that first exposure colored my view of Westerns from then on, as I was non-plussed with the more "standard" John Ford/John Wayne-style material even as a kid. The notion of everything being so clean and orderly and transparent as to whom was the "bad guy" and whom was the "good guy" seemed utterly foreign to me after the dirt and dust and variable ethics of The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly. The former seemed like Hollywood. The latter seemed like life. Having seen many more examples of those styles and more in the years since, I tended to perceive a progression of three distinct periods of the genre and a path of stylistic variance and return, but more evolutionary than periodic.

The classical period

This period covers everything from The Great Train Robbery up to the late 50s. The former was a 1903 film short at a time when fiction about "the Old West" was still a popular pastime in the US. Many of the standout figures of that era, such as Wyatt Earp and Bat Masterson, were still alive at the time and the fictionalization of their various careers had long been established, something touched upon by Eastwood in his Unforgiven, when Little Bill confronts English Bob's biographer about the facts behind the case of The Duke (Duck) of Death.

The mythology of the "Old West" was one based on the hard life that was presented by the frontier, as opposed to the more civilized environs of the East Coast and the original colonies and their urban areas. On the frontier, you had no organized government and lesser respect for the laws that it defended. Furthermore, you had greater threats in terms of exposure, wildlife, and what was presented as the almost-ubiquitous threat of the "savage" Amerindian peoples. Combine all of that with the lack of resources or personal infrastructure of many of the settlers and you had that "harder life" which naturally trends toward stories of great adventure (cue Joseph Campbell's "hero's journey".) The authors of what would later be known as "pulp fiction" were happy to emboss the actually often-mundane realities and gloss over the occasionally sordid details.

This was a tradition that directors like John Ford and Howard Hawks were glad to carry on, whether because it was a personal outlook on concepts like the American/white man's destiny or because they, like the pulp writers, knew what would sell if properly presented (often in that "destiny" vein.) As times moved on in the 20th century, the glorification of the Western frontier, now long past, was also a method of confirming the heroic status of American culture for directors, actors, and audiences. The fact that the frontier life was easily slotted into simplistic moral and ethical scenarios that called for blunt, black-or-white decisions tended to reinforce two things: the concept of frontier people as "heroic" because of their easy acceptance of the way things were (akin to Robert E. Howard's assertion that barbarian ethics, like those of his famous Conan, were superior to civilized corruption); and the anti-intellectualism of those same heroic individuals. Those people didn't need to stop to consider the ramifications of their racial, ethical, or environmental decisions. They were acting that way because the frontier demanded it and, if one wanted to survive on the frontier, then this is how things were handled, especially if you were the "good guy".

As the century progressed and the frontier receded into the historical horizon ("Don't go, Shane!") and began to be overtaken by the possibility of a new frontier overhead, the Western began a transition from the relatively obvious moral decisions of John Ford characters to situations where it became difficult to tell the "white hats" from the "black hats", even using those frontier ethics. In fact, it became easier to associate everyone with "gray hats", especially because that made them... you know... human. It started with a film called Vera Cruz,

Vera Cruz is set during the Franco-Mexican "intervention" and was notable for its rampant cynicism and casual attitude toward violence, which was fairly startling for a movie in 1954. It's considered an inspiration for many later films, including those of Sergio Leone, who is the key player in the real change in Westerns in the 60s. Another contributor to this trend was Warlock.

Warlock presented a situation where the most prominent actor, Henry Fonda, wasn't either the hero or the villain, but more of an "anti-hero". He was still a lawbreaker and was opposed by the genuine "good guy" of Widmark, but it was clear that his intentions were at least nominally good the whole time. This character, more than any other, was predictive of Eastwood's Man with No Name.

The spaghetti period

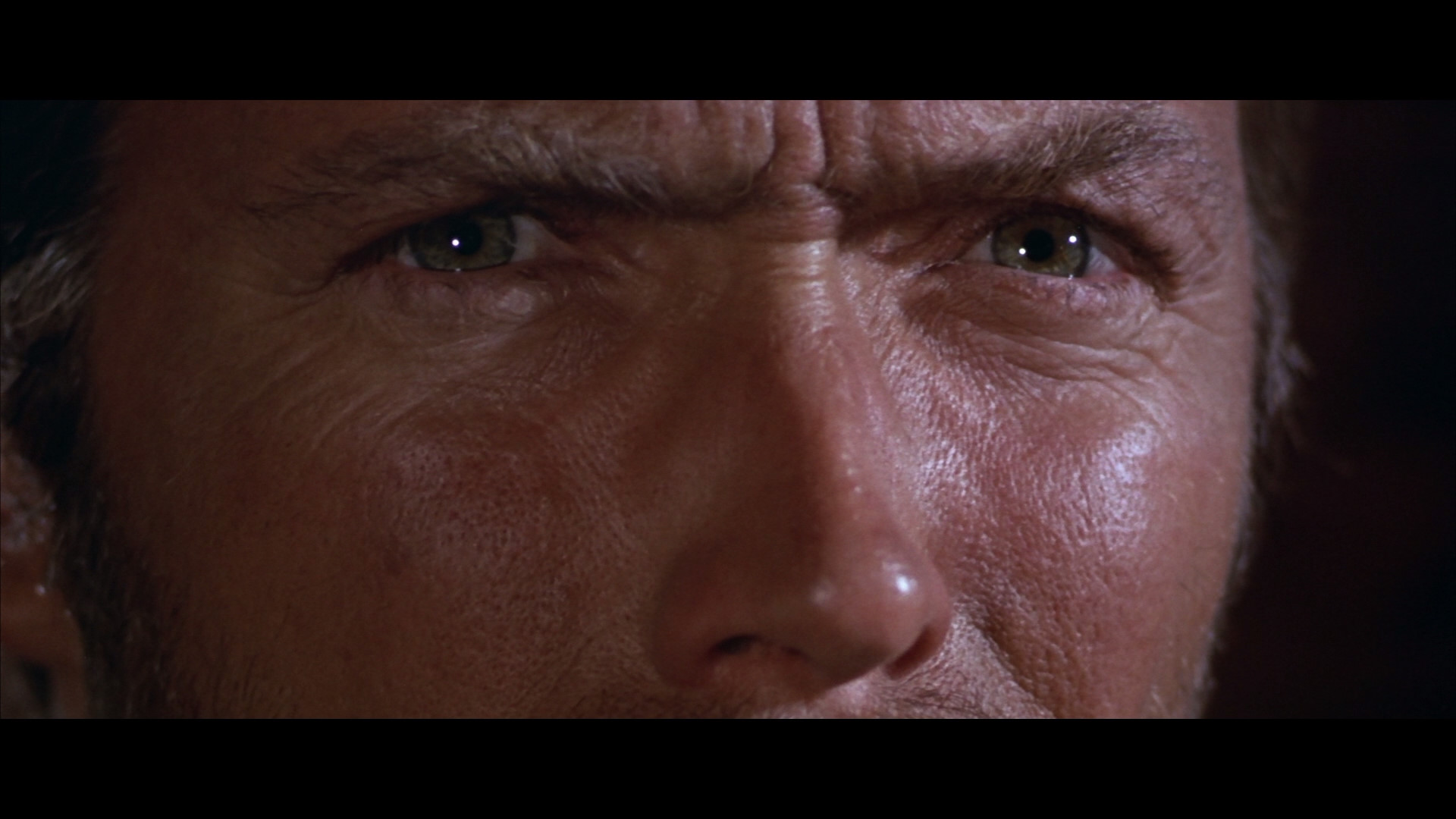

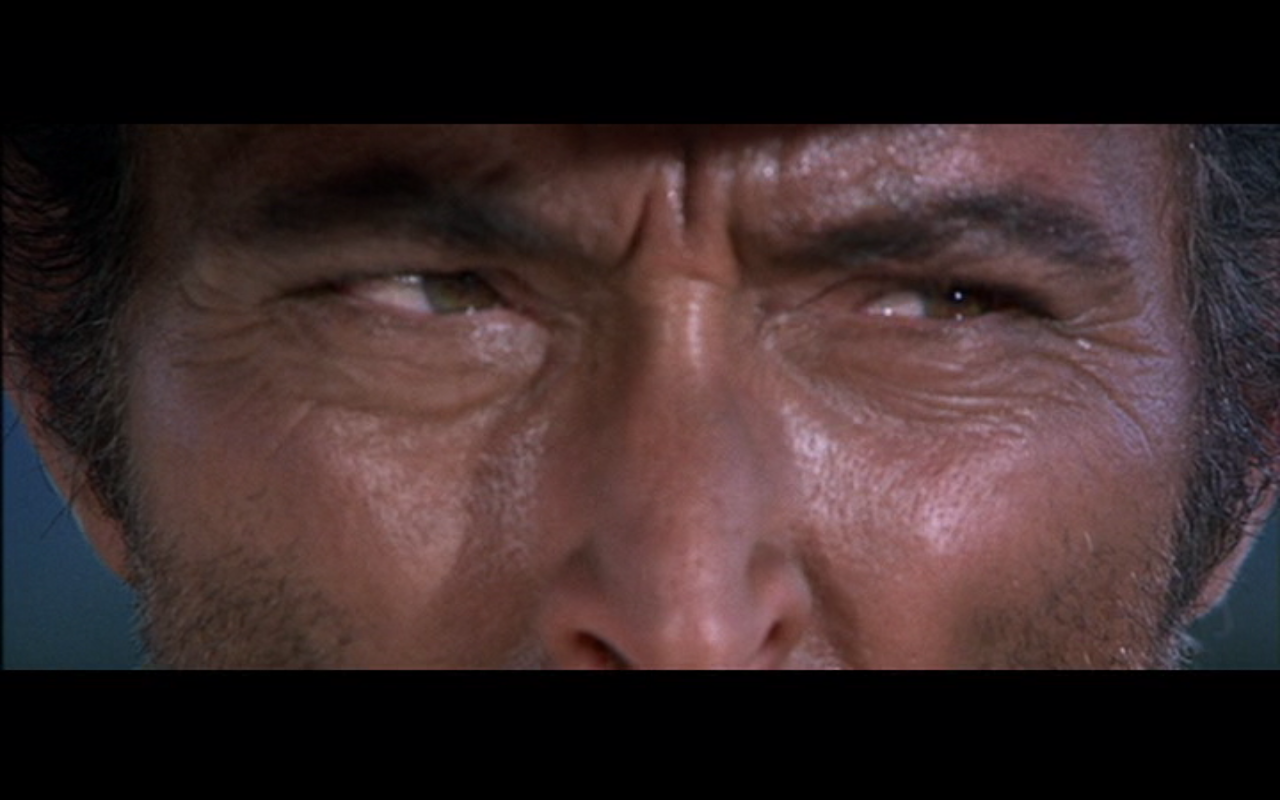

Sergio Leone wanted to do Westerns, but he wanted to do them with a more realistic bent, reflecting the questioning of society's underpinnings that was occurring throughout modern culture during the 1960s. In a curious twist, he and other directors of the time were deeply inspired by Akira Kurosawa, Japan's most famous cinematic auteur who had begun a series of samurai films inspired largely by Shakespeare and... John Ford Westerns! Indeed, John Sturges' The Magnificent Seven was a remake of Kurosawa's Seven Samurai and Leone's A Fistful of Dollars so closely aped Kurosawa's Yojimbo that the latter's producers sued and won damages. Kurosawa's films are notable for many things, but one of the most prominent is the often difficult ethical situations faced by his characters who are frequently having to combat personal mores, as well as those of society. His most memorable characters(in addition to being Toshiro Mifune) are typically loners because of their need to be external to society's strictures in order to be confronted with these situations in the first place. Enter: Clint Eastwood.

A Fistful of Dollars introduced the first truly prominent anti-hero to the American Western genre. Eastwood's character, known as "Joe" (the press would soon tag the Leone/Eastwood trilogy of films as "The Man with No Name" series, even though his character had a name in all three films) seems to be acting in the general direction of "good" but makes it clear that he's most interested in the money and the outcome for the public weal is incidental... except when Marianne Koch as Marisol asks him why he was helping and he makes a reference to his past and a woman he'd once known. So, resolving personal issues or actually doing the "right thing"? That's left to the audience to determine, which is exactly as it should be.

Leone and Eastwood continued their association with For a Few Dollars More and, finally, one of the finest films ever made: The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly.

The Western genre would be changed forever with that trio of films released from 1964 to 1966, but it would take American audiences (and directors) a while to catch on. Other than Leone's brilliant Once Upon a Time in the West, the genre really wouldn't have any significant releases until Eastwood began making his own films in the mid-70s and those drew significantly from an altered assessment of the time period, as well as Leone's genre-shifting work.

The pasta-modern period

Society had moved on from the idea of simplistic heroes and villains. After the turmoil presented by the Vietnam War and Watergate, the presence of a character like the Man with No Name (or the Outlaw Josey Wales) seemed almost a given. Certainly, there were films that attempted to stay within the confines of the Ford/Hawks template and there were homages to that approach, like Lawrence Kasdan's Silverado (which everyone should see, if only for John Cleese's performance as a local sheriff: "As you may have noticed, I am not from these parts.") but most took the more cynical approach of the American public and Leone's take on the genre and began to view it in a seemingly post-modern, constructivist perspective. Not least among these was Eastwood himself, who directly questioned the myth-making of the period with his Unforgiven:

But other fine examples abound, especially those that lifted the genre away from its formerly perpetual obsession with the "unrepentant savages that threatened the frontier way of life", like Dances with Wolves and Geronimo. They appeared alongside films that continued to question the myths surrounding key figures of the period (Wyatt Earp, Tombstone) and remakes that presented their earlier plots in a more intricate skein of people, agendas, and changing times, like the recent 3:10 to Yuma:

In many ways, the modern Western is similar to what the modern gangster movie has become post-Godfather and post-Sopranos: conscious of history and self-aware of the modern perspective that now arches an eyebrow at much of that history. At some point in the future, I'll probably delve back into the Leone/Eastwood trilogy, as those films still carry the most weight for me in the genre as a whole (despite my appreciation for direction and performances, I am not much of an Unforgiven fan, for example.) And, of course, one of these days I should do a post about Kurosawa. And, speaking of Japanese films, watching Godzilla on the 4 O'clock Movie, back in the day...

The classical period

|

| John Ford's Stagecoach, 1939. |

This period covers everything from The Great Train Robbery up to the late 50s. The former was a 1903 film short at a time when fiction about "the Old West" was still a popular pastime in the US. Many of the standout figures of that era, such as Wyatt Earp and Bat Masterson, were still alive at the time and the fictionalization of their various careers had long been established, something touched upon by Eastwood in his Unforgiven, when Little Bill confronts English Bob's biographer about the facts behind the case of The Duke (Duck) of Death.

The mythology of the "Old West" was one based on the hard life that was presented by the frontier, as opposed to the more civilized environs of the East Coast and the original colonies and their urban areas. On the frontier, you had no organized government and lesser respect for the laws that it defended. Furthermore, you had greater threats in terms of exposure, wildlife, and what was presented as the almost-ubiquitous threat of the "savage" Amerindian peoples. Combine all of that with the lack of resources or personal infrastructure of many of the settlers and you had that "harder life" which naturally trends toward stories of great adventure (cue Joseph Campbell's "hero's journey".) The authors of what would later be known as "pulp fiction" were happy to emboss the actually often-mundane realities and gloss over the occasionally sordid details.

This was a tradition that directors like John Ford and Howard Hawks were glad to carry on, whether because it was a personal outlook on concepts like the American/white man's destiny or because they, like the pulp writers, knew what would sell if properly presented (often in that "destiny" vein.) As times moved on in the 20th century, the glorification of the Western frontier, now long past, was also a method of confirming the heroic status of American culture for directors, actors, and audiences. The fact that the frontier life was easily slotted into simplistic moral and ethical scenarios that called for blunt, black-or-white decisions tended to reinforce two things: the concept of frontier people as "heroic" because of their easy acceptance of the way things were (akin to Robert E. Howard's assertion that barbarian ethics, like those of his famous Conan, were superior to civilized corruption); and the anti-intellectualism of those same heroic individuals. Those people didn't need to stop to consider the ramifications of their racial, ethical, or environmental decisions. They were acting that way because the frontier demanded it and, if one wanted to survive on the frontier, then this is how things were handled, especially if you were the "good guy".

As the century progressed and the frontier receded into the historical horizon ("Don't go, Shane!") and began to be overtaken by the possibility of a new frontier overhead, the Western began a transition from the relatively obvious moral decisions of John Ford characters to situations where it became difficult to tell the "white hats" from the "black hats", even using those frontier ethics. In fact, it became easier to associate everyone with "gray hats", especially because that made them... you know... human. It started with a film called Vera Cruz,

Vera Cruz is set during the Franco-Mexican "intervention" and was notable for its rampant cynicism and casual attitude toward violence, which was fairly startling for a movie in 1954. It's considered an inspiration for many later films, including those of Sergio Leone, who is the key player in the real change in Westerns in the 60s. Another contributor to this trend was Warlock.

Warlock presented a situation where the most prominent actor, Henry Fonda, wasn't either the hero or the villain, but more of an "anti-hero". He was still a lawbreaker and was opposed by the genuine "good guy" of Widmark, but it was clear that his intentions were at least nominally good the whole time. This character, more than any other, was predictive of Eastwood's Man with No Name.

The spaghetti period

Sergio Leone wanted to do Westerns, but he wanted to do them with a more realistic bent, reflecting the questioning of society's underpinnings that was occurring throughout modern culture during the 1960s. In a curious twist, he and other directors of the time were deeply inspired by Akira Kurosawa, Japan's most famous cinematic auteur who had begun a series of samurai films inspired largely by Shakespeare and... John Ford Westerns! Indeed, John Sturges' The Magnificent Seven was a remake of Kurosawa's Seven Samurai and Leone's A Fistful of Dollars so closely aped Kurosawa's Yojimbo that the latter's producers sued and won damages. Kurosawa's films are notable for many things, but one of the most prominent is the often difficult ethical situations faced by his characters who are frequently having to combat personal mores, as well as those of society. His most memorable characters(in addition to being Toshiro Mifune) are typically loners because of their need to be external to society's strictures in order to be confronted with these situations in the first place. Enter: Clint Eastwood.

A Fistful of Dollars introduced the first truly prominent anti-hero to the American Western genre. Eastwood's character, known as "Joe" (the press would soon tag the Leone/Eastwood trilogy of films as "The Man with No Name" series, even though his character had a name in all three films) seems to be acting in the general direction of "good" but makes it clear that he's most interested in the money and the outcome for the public weal is incidental... except when Marianne Koch as Marisol asks him why he was helping and he makes a reference to his past and a woman he'd once known. So, resolving personal issues or actually doing the "right thing"? That's left to the audience to determine, which is exactly as it should be.

Leone and Eastwood continued their association with For a Few Dollars More and, finally, one of the finest films ever made: The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly.

The Western genre would be changed forever with that trio of films released from 1964 to 1966, but it would take American audiences (and directors) a while to catch on. Other than Leone's brilliant Once Upon a Time in the West, the genre really wouldn't have any significant releases until Eastwood began making his own films in the mid-70s and those drew significantly from an altered assessment of the time period, as well as Leone's genre-shifting work.

The pasta-modern period

Society had moved on from the idea of simplistic heroes and villains. After the turmoil presented by the Vietnam War and Watergate, the presence of a character like the Man with No Name (or the Outlaw Josey Wales) seemed almost a given. Certainly, there were films that attempted to stay within the confines of the Ford/Hawks template and there were homages to that approach, like Lawrence Kasdan's Silverado (which everyone should see, if only for John Cleese's performance as a local sheriff: "As you may have noticed, I am not from these parts.") but most took the more cynical approach of the American public and Leone's take on the genre and began to view it in a seemingly post-modern, constructivist perspective. Not least among these was Eastwood himself, who directly questioned the myth-making of the period with his Unforgiven:

But other fine examples abound, especially those that lifted the genre away from its formerly perpetual obsession with the "unrepentant savages that threatened the frontier way of life", like Dances with Wolves and Geronimo. They appeared alongside films that continued to question the myths surrounding key figures of the period (Wyatt Earp, Tombstone) and remakes that presented their earlier plots in a more intricate skein of people, agendas, and changing times, like the recent 3:10 to Yuma:

In many ways, the modern Western is similar to what the modern gangster movie has become post-Godfather and post-Sopranos: conscious of history and self-aware of the modern perspective that now arches an eyebrow at much of that history. At some point in the future, I'll probably delve back into the Leone/Eastwood trilogy, as those films still carry the most weight for me in the genre as a whole (despite my appreciation for direction and performances, I am not much of an Unforgiven fan, for example.) And, of course, one of these days I should do a post about Kurosawa. And, speaking of Japanese films, watching Godzilla on the 4 O'clock Movie, back in the day...

Monday, April 16, 2012

Initial thoughts on GoT episode 3 (spoilers)

I suggested to the guys on the board that, since I was no longer reading it, I'd post some thoughts here about Game of Thrones, as many of them have become fans in the last year-and-a-half since the HBO series began. Obviously, there are colossal spoilers below for anyone who hasn't watched or read the books...

I think they conveyed the sense of idleness that permeates the Baratheon/Tyrell alliance. Although the HBO Renly is very different from the book Renly, they both are lacking the same sense of aggression that made Robert the warrior king that he was (or tried to be; far better the former than the latter.) It's all nice and well to assemble 100K men-at-arms and knights, but it's a far cry from an actual army until you have a leader capable of taking it somewhere. Catelyn gets the pleasure of pointing that out on her walk with Renly. Gwendoline Christie was excellent as Brienne, though, and I'm glad they skipped the renaming of Renly's Kingsguard. Given the fact that they're giving free rein to Renly's sexual preferences, rather than overt allusion in the books, the "Rainbow Guard" would have been way over the top. It's a bit much even in the books.

On the one hand, I like that they've introduced Margaery as a smart, capable woman. OTOH, I like the subtlety with which Martin moves her in the books. Even though there is no frank admission of Renly's love for Loras in Clash of Kings, she's presented as clearly knowledgeable about the reality of her marriage and the people around her. Again, this is one of those things that you'd be hard-pressed to imply in a 10-episode TV series (like Melisandre's relationship with Stannis and Craster's arrangement with the Others), so they kind of have to lay it out in the open (as it were.) I think this change to Margaery is unfortunate, but nowhere near as disastrous as the one to Stannis (who was, regrettably, absent from this episode.) With this in mind, it will be interesting to see how they present the Queen of Thorns if she appears next season, as her character is all about subtlety and vague menace. I hope they go into a bit more detail about House Tyrell, as well.

Just like in Clash of Kings, Tyrion is killin' it and, likewise, Peter Dinklage has completely assumed the role of leading man this season. I noticed a lot of people thrilled with his lines and actions in the first two episodes, but this was the one where he really seemed to grow into his own as Hand. The Myrcella situation played out just like in Clash and they preserved a lot of the dialogue, including the moment with Varys ("I've decided I don't like riddles."), which was great to see.

The resolution to the Craster change from last episode was acceptable, although I think they're twisting the "even the good guys make cynical choices in this world" knife a bit too hard. It was obvious when Sam confronted Jon about the fact that Gilly is a person last episode. Having the moment of shock for Jon while Mormont as much as admits that he knows what Craster is up to was unnecessary, IMO. It could have been done much more casually and much faster. We get it, already.

It was certainly good to see Sophie Turner (Sansa) get something out of a script other than shock and dismay. The scene with Shae reminds the TV-only audience that Sansa is still Sansa and not entirely a sympathetic character. I think Shae is being presented as a bit too obvious a fish-out-of-water, though. If this is going to be a secret that is kept from Cersei, the handmaid that flounces around, clearly irritated by her role, is going to be the talk of the servants' quarters pretty damn soon; putting aside the clearly not-Westeros origins.

The Ironborn stuff is still great. Every note of interaction between Theon, Balon, and Yara/Asha has been spot on. While some people complained about the fact that Theon had to be convinced to betray Robb, I think that makes it have more impact. Theon was portrayed by Martin as a petulant irritant from beginning to end (rhymes with 'meek'...), while HBO Theon, although arrogant with the local prostitutes, was showing some genuine ethics and honor in his dealings with Robb. Having to abandon that in order to be accepted by his family makes his decision less of an Eddard-error by Robb and more of a tragedy for Theon. And Aeron Damphair! Woo hoo! But why were the banners gray-blue? Is House Greyjoy so impoverished that they can't replace the banners when they get that badly sun-bleached? Lame.

Bran's scenes were great for two things. First, we got to see Hodor's acknowledgement of it being Bran inside Summer when the latter was walking around. Second, we got to see Maester Aemon actually talk about the maester's chain and its different links, which is a first for the TV show. Isaac Wright-Hempstead continues to impress as Bran, but I find it kind of odd that they still haven't mentioned Summer's name. They, of course, missed the classic line from the first book when he awakens in order to provide a different dramatic moment when Lady is killed last season. But, at some point, you'd think the TV audience would like to know that the wolf has a name.

Finally... Yoren is dead. Too bad. I really didn't care for the character much in the books, but Francis Magee has been brilliant in the past two episodes, sharing the best line honors with Tyrion this time ("I never really cared for crossbows...") Just as Natalia Tena has impressed Martin enough as Osha for him to expand on her part in the upcoming Winds of Winter, one wonders whether Yoren would have gone out so quickly if Martin had had a chance to watch Magee play the role. I think they fumbled the end a bit, as the ordinarily brilliant Maisie Williams (Arya) sounded very wooden when declaring the corpse of Lommy to be Gendry. I think she could have played it sounding a bit more emotional and we could have stopped to look at her while saying the line before moving to the body. But that may be a director thing, as it was the first time for Alik Sakharov in the command chair, even though he's been director of photography on other episodes and many other HBO series.

Anyway, solid episode all around, although I'll be eager to see Dany finally reach Qarth next week.

I think they conveyed the sense of idleness that permeates the Baratheon/Tyrell alliance. Although the HBO Renly is very different from the book Renly, they both are lacking the same sense of aggression that made Robert the warrior king that he was (or tried to be; far better the former than the latter.) It's all nice and well to assemble 100K men-at-arms and knights, but it's a far cry from an actual army until you have a leader capable of taking it somewhere. Catelyn gets the pleasure of pointing that out on her walk with Renly. Gwendoline Christie was excellent as Brienne, though, and I'm glad they skipped the renaming of Renly's Kingsguard. Given the fact that they're giving free rein to Renly's sexual preferences, rather than overt allusion in the books, the "Rainbow Guard" would have been way over the top. It's a bit much even in the books.

On the one hand, I like that they've introduced Margaery as a smart, capable woman. OTOH, I like the subtlety with which Martin moves her in the books. Even though there is no frank admission of Renly's love for Loras in Clash of Kings, she's presented as clearly knowledgeable about the reality of her marriage and the people around her. Again, this is one of those things that you'd be hard-pressed to imply in a 10-episode TV series (like Melisandre's relationship with Stannis and Craster's arrangement with the Others), so they kind of have to lay it out in the open (as it were.) I think this change to Margaery is unfortunate, but nowhere near as disastrous as the one to Stannis (who was, regrettably, absent from this episode.) With this in mind, it will be interesting to see how they present the Queen of Thorns if she appears next season, as her character is all about subtlety and vague menace. I hope they go into a bit more detail about House Tyrell, as well.

Just like in Clash of Kings, Tyrion is killin' it and, likewise, Peter Dinklage has completely assumed the role of leading man this season. I noticed a lot of people thrilled with his lines and actions in the first two episodes, but this was the one where he really seemed to grow into his own as Hand. The Myrcella situation played out just like in Clash and they preserved a lot of the dialogue, including the moment with Varys ("I've decided I don't like riddles."), which was great to see.

The resolution to the Craster change from last episode was acceptable, although I think they're twisting the "even the good guys make cynical choices in this world" knife a bit too hard. It was obvious when Sam confronted Jon about the fact that Gilly is a person last episode. Having the moment of shock for Jon while Mormont as much as admits that he knows what Craster is up to was unnecessary, IMO. It could have been done much more casually and much faster. We get it, already.

It was certainly good to see Sophie Turner (Sansa) get something out of a script other than shock and dismay. The scene with Shae reminds the TV-only audience that Sansa is still Sansa and not entirely a sympathetic character. I think Shae is being presented as a bit too obvious a fish-out-of-water, though. If this is going to be a secret that is kept from Cersei, the handmaid that flounces around, clearly irritated by her role, is going to be the talk of the servants' quarters pretty damn soon; putting aside the clearly not-Westeros origins.

The Ironborn stuff is still great. Every note of interaction between Theon, Balon, and Yara/Asha has been spot on. While some people complained about the fact that Theon had to be convinced to betray Robb, I think that makes it have more impact. Theon was portrayed by Martin as a petulant irritant from beginning to end (rhymes with 'meek'...), while HBO Theon, although arrogant with the local prostitutes, was showing some genuine ethics and honor in his dealings with Robb. Having to abandon that in order to be accepted by his family makes his decision less of an Eddard-error by Robb and more of a tragedy for Theon. And Aeron Damphair! Woo hoo! But why were the banners gray-blue? Is House Greyjoy so impoverished that they can't replace the banners when they get that badly sun-bleached? Lame.

Bran's scenes were great for two things. First, we got to see Hodor's acknowledgement of it being Bran inside Summer when the latter was walking around. Second, we got to see Maester Aemon actually talk about the maester's chain and its different links, which is a first for the TV show. Isaac Wright-Hempstead continues to impress as Bran, but I find it kind of odd that they still haven't mentioned Summer's name. They, of course, missed the classic line from the first book when he awakens in order to provide a different dramatic moment when Lady is killed last season. But, at some point, you'd think the TV audience would like to know that the wolf has a name.

Finally... Yoren is dead. Too bad. I really didn't care for the character much in the books, but Francis Magee has been brilliant in the past two episodes, sharing the best line honors with Tyrion this time ("I never really cared for crossbows...") Just as Natalia Tena has impressed Martin enough as Osha for him to expand on her part in the upcoming Winds of Winter, one wonders whether Yoren would have gone out so quickly if Martin had had a chance to watch Magee play the role. I think they fumbled the end a bit, as the ordinarily brilliant Maisie Williams (Arya) sounded very wooden when declaring the corpse of Lommy to be Gendry. I think she could have played it sounding a bit more emotional and we could have stopped to look at her while saying the line before moving to the body. But that may be a director thing, as it was the first time for Alik Sakharov in the command chair, even though he's been director of photography on other episodes and many other HBO series.

Anyway, solid episode all around, although I'll be eager to see Dany finally reach Qarth next week.

Thursday, April 5, 2012

A long, long time ago in a town right nearby

I used to attend shows like this and think that I would be making my way in the industry:

Comic Con has changed quite a bit and I am more distant from it than ever.

Comic Con has changed quite a bit and I am more distant from it than ever.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)