The definition of class standing is often a moment of awkwardness in discussions among Americans. Few people want to admit to being "wealthy" because that involves an inherent conflict of perspective when associating with those who aren't. Likewise, most people aren't eager to announce themselves as "poor", because of the similar social stigma. Back in the Old Country, it was simply accepted that those who were of the noble class were simply superior humans (Star-bellied Sneetches) to others and both sides were more or less comfortable with that arrangement (or had to be.) This kind of division had been handed down in many ways from the Roman Republic's patrician and plebeian divide, where the former class, even if its members weren't wealthy, had certain rights that placed them above the "commoners". That system, like that of later Europe, eventually became fuzzy around the edges, as wealthy New Men, like Gaius Marius and Marcus Licinius Crassus, later demonstrated just how foolish the idea of genetic superiority was (Yes, we still have a problem with that...) It was, of course, later revived in the Dark Ages like so many other things that had been dismissed.

In the US, there has nominally never been a "noble" class... unless you were White. And male. And a landowner. But aside from all of that, the ideal of the American experiment was that social mobility was key and anyone could be whatever they wanted, so long as they worked hard enough. This is The American Dream. As the US was founded as a moneymaking venture and has never departed that classification, the idea of social divisions was based solely upon that more practical divide that people like Crassus once used to their advantage: money. The "highest" social class in the modern American perspective is that of "middle class", since one can access pretty much everything that one wants (and certainly everything one needs) and not be seen by the bulk of the population as being part of the ownership class, who are the ones properly reviled for making/writing/altering the rules to their own advantage; typically to the misery of the rest of us. As part of the middle class, one can be comfortable and still qualify as Average Joe. It's a conceit and a pretty obvious one, but it's a tiny part of the vast illusion that so many carry about the success of that American experiment.

That's what makes the Robert Frank article yesterday on CNBC's site, spotlighting the ruffled feathers of the ownership class about Joe Biden's proposed new tax plan, so funny. First off, let's start with the idea that an income of $400,000/year defines one as "middle-class." (Why the hyphen? I don't know.) This ludicrous concept is solidly refuted within the article itself, as it points out that said income places one in the top 2% of income earners in the nation. Given a scale from 1 to 100, I'm willing to bet that most people would define the "middle" of that as somewhere within shouting distance of 50; such that "middle class" would be, say, the middle third, roughly 36 to 75% or so. That, of course, would plunge a number of people into those labels that they're eager to avoid: "upper class", "wealthy", "rich", and so on. This is, again, mirrored by those not wanting to define themselves as "lower class", since the shine of being a blue-collar worker on the lower end of the income scale has been rapidly rubbed off over the past half-century. It's not so much that people are doing "honest" or "necessary" work for lower pay (we can talk about the societal morality of that some other time), as much as it is that being perceived as "lower class" is part of being among those who have "failed" in America. Thus, everyone aspires to be "middle class" so that everyone can be the same and, of course, be treated the same just like all Americans are treated, right? Right? Tell it to a woman when the topic of salary comparisons comes up. Tell it to a Black person when the topic of treatment by police comes up.

|

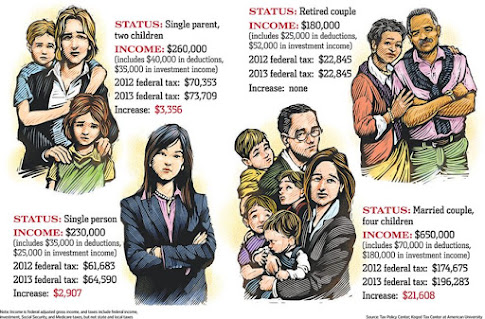

This is from the Wall Street Journal, the last time Obama was seriously talking taxes (2013.) Extremely tough going for that single person making a quarter mil and needing to drop another $3K. |

But let's get back to why Robert Frank has decided to take the ownership class' perspective on the concept of being "middle class". Let's start with the obvious: The real target of Biden's prospective plan is the super wealthy (i.e. the top .1% of income earners.) But that doesn't mean it stops only there. Thus, the acknowledgment that those who make $400K or more are, in fact, wealthy. CNBC attempts to refute this by suggesting that, since those "middle class" earners aren't driving a Lamborghini, they don't deserve to be labeled as such. (A friend pointing out this farce also informed me of the cost of an oil change for that line of cars. Life is rough.) He follows swiftly by citing the fact that less than 2% of the nation's population earns 25% of its gross income. If one is trying to make the point that the "middle class" is already burdened enough, this is hardly the way to start. And, as always, let's be sure to keep in mind the difference between income and wealth; the latter of which is often more difficult to quantify but which represents a significant factor in the difference between the wealthy(!) and everyone else. He reinforces this rake-stepping assessment of the obvious by pointing out that $400K is six times the national median (hardly "middle class", then, right?) and even three times the median in high-cost locales like New York and San Francisco.

This is immediately followed by the disclaimer that living in one of those high-cost cities means that $400K doesn't really go as far as you'd think (still 2 to 3 times the median!) when under the following definition of "middle class":

“Based on the expenses, a $400,000 household income provides for a relatively middle-class lifestyle,” Dogen said. “A middle-class lifestyle is defined as: owning a home, having two kids, saving for retirement, saving for college, going on modest vacations several weeks a year, and retiring in one’s early 60s.”

From a personal perspective, I've always considered myself to be somewhere in the vicinity of middle class because even when I (or we) was struggling to make ends meet, I still had enough for things like cable TV and wasn't in crisis mode when it came to paying the rent or putting food on the table. That's how I define "middle class." I've owned a home once in my life. It was a net negative to our income, because it meant that our housing cost basically doubled over the amount of rent we'd been paying previously. Oh, but the tax benefits! was the answering refrain when I brought up that point. Yeah, those tax benefits occurred once a year, but I was paying that mortgage in the 11 other months. I've never worked a job that paid me enough to seriously consider the idea of substantially saving for a child's college expenses (this doesn't even consider the outrageous cost of 4-year universities, currently), to say nothing of two. I've also rarely had a job that let me save for more than roughly six months of "retirement" expenses. Most so-called "middle class" jobs start at one or two weeks of vacation. If you stay there for 10 years, maybe you'll climb up to three or four. None of those qualify as "several weeks a year", be they "modest vacations" or not. Am I, then, not "middle class"?

But Frank argues that middle class folks who clear $400K/year (aka more than I've made at most of my jobs in almost 10 years) aren't doing so well, considering the mortgage on their $2 million home... So, why does their home cost $2 million as a "middle class" person again? Is it because they live in San Francisco? Well, that's a luxury good/choice, right? According to CNBC, even if they do make that luxury choice, they're still making 3 times the median income there, right? And they're still dumping what was close to an entire year's salary for me into their 401K, right? That sounds pretty damn wealthy. The fact that you spend every dime you make (except for, you know, the $40K going into a retirement account every year) doesn't make you unable to live the high life. It just means that you've made choices that make you cash poor in order to subtly signal your status (home worth $2 million in NYC), while you can claim to be more affected than you could be. People enjoying this special CNBC status are what the Russian peasantry used to call kulaks, peasants that had become landowners themselves, although that term originally meant "tight-fisted", which is not what's happening here.

And, of course, the genuine irony here about CNBC's definition of "middle class" is that all of those assertions that they make about that status were what Average Joe used to be able to do. When the unions were strong from the 40s to the 70s, they actually could work blue collar jobs and still send their kids to college, own a home, take vacations, and so on. A lot of people working the "white collar" jobs like I've done could do the same. We could do these things because the power of collective action meant that the ownership class was forced to acknowledge the value of both our labor and our identity as human beings. Since the Reagan era, that has been less and less of a concern to the wealthy and most Americans have been indoctrinated into their religion, as well. The ownership class became disturbed that lesser people could enjoy that fabled American Dream and decided to reorient the public's perception of who deserved what. Instead, what we now have is this:

What that basically displays is the number of weeks the average male worker needs to work in order to afford major expenses (housing, health care, education, etc.) In 1985, it was 30 weeks. In 2018, it was 53. It hasn't gotten better. It is, of course, even worse for women: In 1985, it was 45 weeks (just barely enough for those "several" weeks of vacation!) In 2018, it was 66. This also doesn't include other necessary expenses like food, clothing, utilities, and maintenance of those major expenses. It also comes equipped with the assumption that emergencies will never occur and, of course, that retirement will never, ever happen.

One thing to keep in mind, though, is that those same kulaks in early 20th-century Russia were believed to be tentative allies of the revolution, because they recognized the vast gulf that remained between their life of relative comfort and the resplendence that the top of the pyramid enjoyed. That may be the case here, as well, since the central theme of control always employed by the ownership class is turning one segment of the population against another; whether it be by differences of income, skin tone, religion, or otherwise. It's useful to keep in mind the source of this article and the type of America that they're most interested in promoting.