So, I finally got around to sitting down in front of The Avengers yesterday. Overall, I was OK with it. It was fun, as most of Marvel's movies are supposed to be. Character-wise, once again, Robert Downey, Jr. was the highlight as Tony Stark/Iron Man, as he's the best actor among them and had the best lines. I think that Chris Evans (Captain America) and Chris Hemsworth (Thor) do solid jobs with what they're given to work with. On that note, Jeremy Renner's role as Hawkeye was pretty monochromatic, which is a shame for a guy that did really well in The Hurt Locker and The Town. You'd hope for something a little more emotive, especially from someone playing Clint Barton, a rather tempestuous character in the comics, but it was not to be. Thankfully, they left out the goofy purple-and-blue costume with the big "H" on the forehead, just in case people forgot who he was. ("Of course! He's H-Man!")

By the same token. Tom Hiddleston was unfortunately stuck with Loki's classic golden-stag-on-PCP uniform. It's not like subtlety has ever been a large facet of the character and Hiddleston plays it for all it's worth, but you still kind of wonder at that choice. Mark Ruffalo was actually really good as Bruce Banner (Here's a bit of cultural trivia: Why was the character named David Bruce Banner in the 70s TV show? Because Universal thought that "Bruce" was a name too closely identified with gay men. I kid you not. There was even a joke about it in a contemporary issue of the comic where Banner is checking the classifieds for jobs and sees an ad for "Turkish baths" and thinks to himself: "Nah. I don't think that's for me." My reaction as an 8-year-old: "What's a bathhouse?") Scarlett Johansson (Black Widow) is herself: she's wooden, she's gorgeous, I could watch her beating the crap out of Russian mobsters all day:

and Sam Jackson (Nick Fury) continues his string of roles that will never even approach his stellar performances in Pulp Fiction and The Red Violin. It's a shame, really, because you'd think with the ethical conflicts inherent to the role (and squaring off on SHIELD's version of Skype with a shadowy Powers Boothe), he'd have a lot of room to work.

I think the script was pretty uneven, though. There were moments when someone was gabbling on about this or that topic where I was actually waving my hand as if to hurry the pace because it was pretty tedious. I don't know whether that's an effect of my knowing all of this stuff (The "tesseract" is the Cosmic Cube, which was created by AIM (Advanced Idea Mechanics) with a biological computer named MODOK (Mental Organism Designed Only for Killing; why, then, was he created to create the Cube...?) It was later used by the Red Skull to try to kill Captain America and was lost by him to the Sub-Mariner and later reclaimed by the Red Skull and later stolen from him by Thanos (the grinning, purple dude at the end), who was the only person able to truly exploit its power to reshape reality ("It's a genie in the lamp. But with a thousand wishes. And in cube form.") and try to reshape the universe and... on and on and on...) There's a lot of backstory here, most of which they dispensed with based on a tale about perpetual energy, which is a nice shortcut and certainly more relevant to a modern, movie-going audience (AIM always looked liked dorks in those yellow outfits, anyway)

but part of taking that shortcut with an ensemble cast is that you have "character stuff" that has to come to light which can't really be done as anything but boilerplate exposition, lest you lose the pace of the film. They almost did that a couple times, anyway.

It was interesting to see them run across the same problem that most comic writers did in the 80s: How do you rationalize the Batman-types (Hawkeye, Black Widow, Captain America) fighting against things that would actually provide a challenge to the Superman-types, like the Hulk and the God of Thunder? You could kind of dodge that when people didn't pay too much critical attention to stuff like, you know... story in the 60s and 70s but it became more difficult later. I still found it kind of ludicrous that, in a battle taking place across all of midtown Manhattan, the three "human-powered" types would think that whatever they were doing in one intersection would have any effect on the thousands of lives endangered by a constant flow of homicidal aliens on personal hovercraft, not to mention the gigantic flying Moray eels/troop carriers. This is where you run into the conflict between character and story that is reminiscent of what I mentioned in this post: "character" is for long-time readers; "cool SF stories where lots of stuff blows up" is often for new readers. In the movie business, it's a microcosm of the same thing and it's all about pacing.

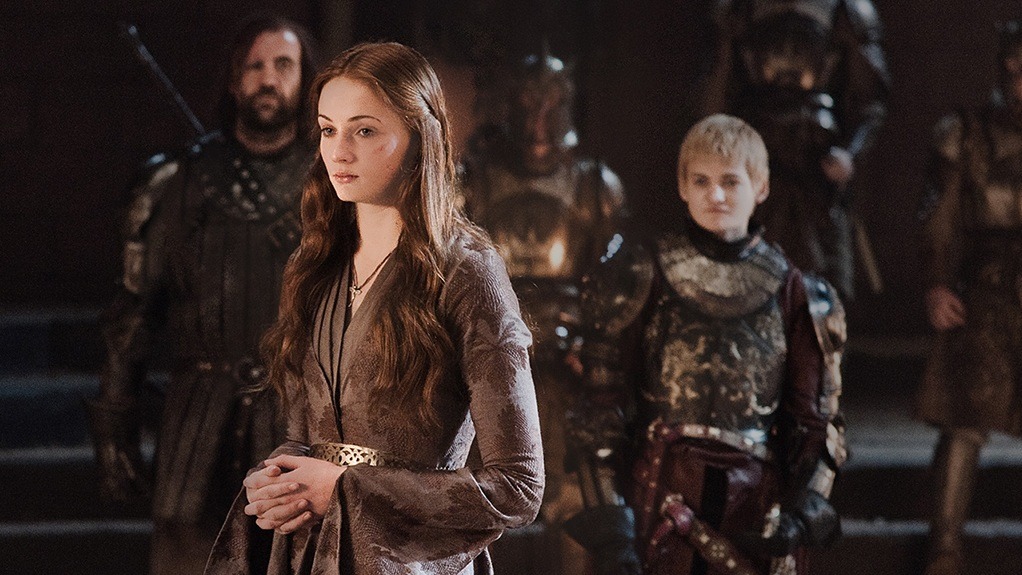

I have no concrete opinion on Joss Whedon. I've seen almost none of his TV work, although I have many friends who swear by Buffy and Firefly, the latter of which I've seen a couple episodes of and which seems to me to be remarkably overblown, but cult audiences are labeled so for a reason and I'm as guilty of it as anyone else. Having seen Serenity, I'd say this is a step up in that it retains his often deft touch with dialogue and humor, but maintains a better handle on the cuts from one point of the ongoing battle to the next. He also handles the sadly obligatory "superheroes meet and beat the crap out of each other before actually talking" encounter about as coherently as you can. He shows a nice touch in this scene, which expresses and releases some of the audience frustration with the slippery villain (and is, without doubt, the funniest of the movie):

The audience laughter overwhelms the Hulk's one actual line in the film, which is the only moment when Whedon gets away from the fact that the whole "Hulk, Mindless Savage" perspective came from the aforementioned TV series. That trope gets old fast, which is why I appreciated the fact that Lee and Kirby originally designed the Hulk as more of a tragic figure. He can talk, if somewhat haltingly, and spends most of his time doing so asking why people keep shooting him for no other reason than he's big, green, and didn't do what the Pentagon told him... He was intended to be a modern spin on Jekyll/Hyde, except that he was misunderstood, as opposed to showing the darker side of humanity. My one real hope was that they would start steering the character back in that direction. This may or may not have been the first step in that process. Am I the only one who thought of a dog trying to shake the life from one of his lifeless toys in that clip?

Bitch, bitch, bitch... I know this all sounds like I'm trying to shred the film but I actually did like it. I'm just so pre-wired to most of this stuff that it's hard for me to look at it with anything but a very jaded (Radioactive Man?) eye. I've read more superhero comics than most people should be in the same room with. Bottom line: if you keep your expectations at the level of "superhero film", you will not be disappointed. I still think Iron Man is the best of the recent offerings by Marvel and the only one that rises above said level. I'm still astounded that The Avengers has been so well received by critics, but I can certainly understand being swept away by the (perpetual) energy. The fact that they've indicated that Thanos is the villain of choice for the sequel fills me with varying degrees of dread. Had this been the early 80s, I'd have been thrilled, but there's been a lot of crap piled on top of that character since then. So, we'll see. Of course, I do have to say that one of the best moments of the film is the shawarma bit after the credits,

if only because it conveys that atmosphere of what it must feel like to have been thrown through a few skyscrapers for a couple hours. The impressive restraint is indicative of Whedon's potential as a director and may indicate an ability to demonstrate that further in the sequels. Here's hoping.