There's a fair amount to be said about The Dark Knight Rising and much of it has to do with trends in the source material: the Batman/Detective comics that have been published for almost 75 years now. I think DKR was a solid movie, but I can't say it was a great one. I think it is the weakest of the Nolan trilogy, but still vastly superior to anything done by Burton or the wretched sequels that followed his efforts. Part of that is an appreciation for the character's roots and part of it is clearly an appreciation for its (relatively) very recent history. Significant spoilers below.

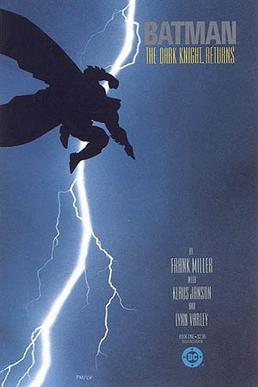

No matter what anyone tries from this point forward, they will likely never be able to escape the presence of Frank Miller's The Dark Knight Returns mini-series. Along with Watchmen, it heralded the beginning of the "grim and gritty" era of comics in the mid-80s. Those books grounded comics in "the real world"; they were emblematic of the way people talked and thought and lived in the 1980s, not some upgraded version of the 1950s that most superhero worlds inhabited. Despite dealing with drugs, sex, and racial issues from the late 60s onward (Marvel's Amazing Spider-Man #96-98 in 1969 essentially broke the Comics Code publishing authority by including a story about the detrimental effects of heroin addiction; the authority essentially ceased to be relevant from that point forward) and despite Neal Adams and Denny O'Neill having restored the Batman to his dark roots in the early 70s in an effort to escape the 1960s TV show, the culture of the worlds that comics created were still outside the realm of the everyday. They were still too staged and too preoccupied with super-powered explosions.

Then came Watchmen, firmly grounded in the Cold War and humanity's natural tendency to fear and hate whatever it didn't understand, including those weird people with the masks and very unnatural abilities. The Dark Knight Returns also rode that wave, pursuing the idea that the Batman along with those like him had been outlawed many years before, leaving a bitter and spiteful Bruce Wayne to watch Gotham City sink into chaos. In Miller's story, he attempts to save it from the utter destruction visited upon it by the gangs that control it. The Joker returns and the public blames the Batman for his actions. In the end, all-out war takes place on the streets, as different factions vie with each other and the Batman attempts to keep order, while ducking the government's attempts to capture him (with Superman, no less.). Along the way, the only person defending him is the now-forcibly-retired Commissioner Gordon. Sound familiar?

Miller reflected society and what would be at least some of the prevailing impulses and responses to a costumed vigilante. Nolan's scripts reflect this, as well, because the movie-going public will not swallow the basic reality that the comic-reading public often accepts: that seeing Spider-Man swinging down the street in pursuit of Electro and having the Batman beating the crap out of Killer Moth outside your restaurant is simply the natural order of things.

I think that the Nolans' script continues to embrace Miller's perspective (as I mentioned before, Batman Begins borrows heavily from Miller's Batman: Year One), but they've also demonstrated a willingness to adapt that perspective to tell their own story about a man so possessed by vengeance that he would sacrifice his fortune, his life, his friends, and his body in order to fulfill it. In the process, they've come full circle on that quest and shown the ripple effects of its outsized ambition. I like that. I appreciate that they showed the blowback, as it were, rather than simply dismissing what has gone before as last issue, which will only become relevant when the surely-dead major villain miraculously appears alive.

Interestingly, Bane as a character was essentially an homage to Miller's work, as well. In the second issue of The Dark Knight Returns, the Batman is beaten to within an inch of his life by the leader of the Mutant gang. He eventually returns the favor and breaks the will of the gang by defeating their leader (assisted, incidentally, by a version of the Batmobile that is more tank than car; yes, that's Miller, too.) This was the first time that Batman had been seen to be physically overmatched by another human, albeit one that was, as Wayne himself noted in the story "faster, stronger, and younger than [me] by 20 years." I think that inspired Denny O'Neill, who was an editor in the early 90s, to develop the idea of a character that would "break" the Batman, physically and mentally. Thus, Bane was developed as one of the early 90s massive crossover/super-platinum cover events which dominated the market (and almost destroyed it later in the decade) and still does to one degree or another.

In other words, Bane is a cipher. He's a plot device. He doesn't really have a motivation other than to break Batman's back, which he does, releasing chaos onto the streets, while the Batman is replaced by an almost-equally psychotic disciple for a few months until miracle surgery can be performed to return him to Gotham to defeat both Bane and the new Batman. It was all rather trite and redolent of spectacle over story... which is why I think that, despite some of the nice turns that Nolan put into the script to create Bane as something more than a device, the story still falls behind the prior two films. The central threat is not driven by anything that most audiences will be able to either relate to or even care about and, fittingly, Bane is removed from the film by a casual blast from the Bat-pod driven by Selina Kyle and, presumably, dies off-screen somewhere. In some respects, it's appropriate because, of course, the true driving force behind the whole threat is not Bane, but Talia. It's also appropriate in that, at it's root, the story is not about Bane. It's about the Batman/Bruce Wayne. But the reason that The Dark Knight worked so well and the reason that Batman/Detective comics have lasted as long as they have is that the Batman is not so much the protagonist of his adventures as the antagonist. The audience/reader wants to see the crazy stuff that the Joker, the Riddler, and the Scarecrow are going to engage in. They want to see inside the mind of the insane. The single-minded force of reason (the Batman) is already understood. What's interesting is to explore the other side. In Rising, Bane doesn't supply that because he's still more tool than character, which is a shame.

Things I liked

I like that they included Talia. She had always been an element of stories surrounding Ra's al Ghul and it's appropriate that Nolan hewed close enough to the source material to make her the driving element behind the master scheme. It's also nice to see a very capable and intelligent woman in the recent parade of superhero movies (they haven't been entirely absent, but they haven't been foci, either.) One wonders if Marion Cotillard will approach Nolan about being something less than a mildly-crazed destructive force for his next film, since that seems to be her trend. Nothing wrong with playing a villain, of course, as I tend to follow Dark Helmet's dictum on that. While the sexual/love interest contact between her and Wayne was as contrived as ever, it was nice to see their nod to that element of the two characters' relationship, which has been present since Ra's was created by O'Neill in the 70s. (Incidentally, the name Ra's al Ghul means "head of the demon" in Arabic (after the "demon star", Algol) and it's pronounced "raysh", not "rahs". Given their otherwise spectacular attention to detail, I wonder why that's never been corrected.)

I like that they never once referred to Selina Kyle as "Catwoman". The fact that her IR goggles when pushed back on her head resembled a cat's ears seemed playfully coincidental. Hathaway played another intelligent, energetic, and capable female character and it was, again, good to see them slip in the romantic attachment that has been an element of Selina Kyle since she was first created (as "The Cat") by Bob Kane and Bill Finger in the 30s.

I liked the reduction in explosions. While there were still plenty to be had, the Dark Knight became a bit glutted by fire and shock waves to the point of tedium. More of the action in Rising was reverted to plain, old Batman fisticuffs, which can be tiresome in its own right, but was broken nicely by multiple perspectives and a lot of motion. One of the previews prior to the film was for the latest film incarnation of Resident Evil. I'm fairly certain that no more than two seconds elapsed at any point during the 60-second clip before yet another incendiary or propulsive display took place. That one got the greatest Sigh Factor™ for the day.

I liked the inclusion of contemporary issues and the public questioning of how the average citizen will survive while the owning class revels in their own existence.*

I think all of the performances were solid. Bale's was probably his best of the three films (one wonders if the Oscar win for The Fighter was his light bulb moment) as he certainly seems to have grown, not just in this role, but in his craft, overall. I continue to think that Gary Oldman is criminally underused in the staid Commissioner Gordon role, but there's something to be said for versatility (akin to Helena Bonham-Carter's performance in The King's Speech.) It was good to see Cilian Murphy return as Jonathan Crane for a few minutes. That was also a nice nod to the Robin legend at the end which was, thankfully, kept off-screen and served as a fitting pass of the torch to whomever takes up the writing/directing chair(s) in the future.

Things I not so liked

The script was uneven. There were some good lines (Hathaway seemed to get the best of them) and the characters remained as real as in the prior films. But there were some heavy expository moments that didn't involve philosophical outlooks so much as rote re-telling of origin stories or some such thing that you hoped would be shown more than told. Furthermore, there seemed to be a lot more "comic dialogue" than was present in the earlier films. When the Batman first encountered the Joker in The Dark Knight, he didn't stop to blurt out the latter's name so everyone in the crowd would know who it was. Everyone knew that already. Yet, in Rising, when he first encounters Bane, despite being aware of who he is and the audience already being fully educated, Bale stops and delivers the dramatic line: "Bane." I sat in anticipation of the Image-style posing shot before the ego-massaging/face-beating commenced.

Despite the capable direction of the action sequences, I think we've reached the limit of where the "real-time fighting" can take us. Half of the Bane/Batman engagements seemed to be a version of E. Honda's Hundred-Hand Slap: there were clearly a lot of strikes, but you didn't know where they landed or sometimes who threw them. Having practiced martial arts for a number of years, I've come to appreciate films (and actors) who've taken the time to engage in actual techniques that clearly do something other than just batter the opponent like a hailstorm. I can see the aikido and the jiu-jitsu and the escrima that Jason Bourne uses and I can see the kickboxing that Martin Blank uses in Grosse Pointe Blank; mostly because I can see them throwing punches and can see where they land. While it's all well and good to convey the speed and urgency of the encounter, I wouldn't mind going back to a little choreography that could actually be followed.

Perhaps it was simply the poor sound equipment of the theater or the position we were in relative to the speakers (we saw the IMAX version and ended up pretty close to the screen) but I heard a ton of reverb and feedback that frequently overwhelmed spoken lines. The ominous bass line of the soundtrack didn't help with this at all and, of course, the fact that Bane's voice was already distorted meant that I spent a fair amount of time trying to decipher what he said rather than simply listening to what he was saying.

On the topic of Bane, I failed to understand the whole mask backstory. The original character wore a mask for the same reason the Batman does: to intimidate his opponents. What gave him his power was a drug called Venom that was injected directly into his brain.

That's why you can see cables wrapped around him in most of his pictures from the comics. In Rising, we were presented with the idea that Bane's face had been ruined in prison and he took drugs from a unit directly attached to his face to save him from the pain of... bad dental work? The pain suppressors are what enable him to break concrete pillars by punching them? I have a hard time believing that his voice couldn't have been altered in the same way that Bale's is when he's in costume. Perhaps I'm just missing something.

*That said, I expressly disliked the idea that the revolt of the average citizen against the wealth that owns them was somehow necessarily driven by a nihilistic savage and was, therefore, implicitly wrong. Given that significant social change and some degree of justice in this country is unlikely to occur without violence, one doesn't need a terrorist and a fusion bomb to effect it. One really only needs Mitt Romney and Barack Obama as the only two sides of the argument about how many of the underclass should be sacrificed for a couple more million to flow to the top percent.

So, overall, I wouldn't call it one of Nolan's stronger efforts, but I think it was a decent end to a trilogy that will have lasting positive effect on the character and its legend for most of the public. I'd certainly recommend seeing it if you enjoyed the prior films, but it's not a must-see if you're just not into the whole Caped Crusader thing.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.