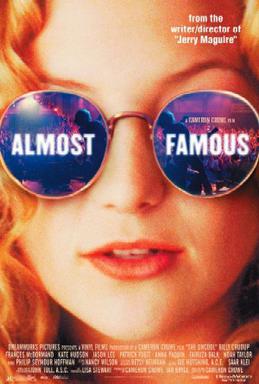

But I think the reasons it really appeals to me are two-fold. First, it's about music and the kind of devotion and enchantment that music can create, both among its creators and its fans. To quote Crudup: "My last words were [and mine may be]: I dig music." Jeebus, I listen to game soundtracks because of the twinges my soul gets from a nice violin piece. It's that bad.

But, secondly, it's about a bunch of creative people enjoying that process together, no matter where it took them. The comic studio was like that in many ways. We weren't reaching the big time. We never made any money. But it was never a bad time and I was committed to making it become... something. What, I'm never quite sure, but I was committed. That should be a startling shock to any of you that know me.

I met Jeff Donaldson in 1991 at the Chicago Comicon. I had already lined up my friends, Will Kliber and Wendy Law, in my quest to become a successful comic writer; nominally for DC or Marvel because they were, as they are now, the biggest kids on the block. I was shopping stuff around to other places/players (Dark Horse, Comico, Majestic) but hadn't gotten a bite and Image had just emerged on the scene. The comic world was just beginning to boom past its geeky, shadowy existence and there were a dozen hundred startups of all kinds at the big shows, where Dave Sim was lord of the small press manor. I vividly remember some kids drawing stick figures in a quartered letter-size piece of paper and selling them for $1.50 each. Hey, if Matt Feazell could do it with Cynicalman, why the hell not? The irony is thick and tendentious...

Jeff and Dave Witt and a couple other artists were making a scene in the small press area of the 1991 show and Will had met them on Saturday while I was still trying to make inroads with the bigger houses (this is where I first met up with an editor at Majestic who was more interested in sleeping with me than publishing my stuff; inroads being what they is, I kept in touch with her, show after show, for the next couple years until Majestic collapsed and died with the rest of the industry.) Will steered me over to them on Sunday and we talked about producing some stuff on an actual deadline for their studio, Fifth Panel Comics. As usual, Jeff was in no way serious about that deadline. I was deadly serious and hounded Will about the details of a 12-page neo-Gothic horror story involving a character called The Gargoyle (stunningly innovative) over the next few weeks. The kernel of that character came from a House of Mystery reprint I read in the late 70s (I forget nothing) and I had grand plans to turn it into something which it never became, while I continued to schlep even grander plans to outfits bigger than 5th Panel.

But those Grandiose Adventures never got sold and Jeff and I talked almost every day and it wasn't long before Fifth Panel started to become the focus of my comic world. This world, at least, since there are infinites, as you and I well know. However, everyone at 5PC was doing their own world and, since I was still very sold on the idea of the group thing that Almost Famous so vividly represents, I suggested making a group world that everyone else could pitch their own thing into and we could all reach that pinnacular moment that we all wanted to reach, separately AND together, and oh my wouldn't it just be so fine...

Jeff smiled and said: "Sure."

Interpreting his casual enthusiasm as a deadline of the most extreme sincerity (in this, I am Patrick Fugit), I sat down a couple days later and spewed out a couple dozen pages of outline with several dozen characters, a few hundred stories, and a few thousand possible storylines dangling off of it in an afternoon. My girlfriend came over at one point to see me, at which time I rather brusquely informed her that "I'm working." My shirtless, unshowered, fairly diffidently-gazed self probably indicated that, but I had to be sure. I couldn't be disturbed. Actually, it really wasn't that difficult or intense. I just had to be sure that she was aware that the creative process was in motion. It felt like the right thing to do at the time. Very Hunter Thompson.

That evening, I drove up to Jeff's place in White Lake and dropped the outline in front of him. He nodded, sagely (we were still kind of feeling each other out in our respective roles), and started reading. A couple pages in, he picked up the phone and called one of the studio's artists:

"Hey, you should get down here and read this cool outline that Marc wrote up for a shared world."

A couple more pages. Another call.

"Hey, you should really come over here and read this awesome outline that Marc put together."

A few more pages. Another call.

"Dude, get down here and check out this amazing stuff that Marc put together."

From that point on, Jeff and I were on the same page(s). Our lives weren't very similar. He had a career at Chrysler and was starting a family. I had a series of bullshit jobs and hung out with other political miscreants, theorizing about the revolution. But we shared a passion and conveyed it to a gaggle of artists and other comic-types who then joined us for our various road trips to locales around the Midwest and East coast. The small press scene was booming as the comic industry was booming on the fuel of speculation and we were going to ride this wave as long as we could. One day, Jeff would retire from Chrysler and become the full-time publisher, but a long time before that, I'd be writing my stuff and editing the rest of the studio's output to genuine comics glory.

At the time, we were assembling our books by hand, a group of us stalking around a table in Jeff's attic ("the studio"), drinking and swaying to Beck's Soul Suckin' Jerk, as we grabbed pages, folded, and stapled. There was no better way to spend an evening.

Our road trips were almost always excursions preceded by frenzied activity to pack all of our latest material and Jeff's latest updates to the booth into a minivan that he'd borrowed off the Chrysler lot (the really cool moments were when he borrowed a Viper to come down to Ann Arbor so we could talk studio work and then try to take it airborne on Michigan Avenue.) When we hit the shows, the object was to be as loud and obnoxious as possible to separate ourselves from the other two dozen small studios packed into the darkest and/or remotest corner of the major convention space or to be the one studio that stood out at the inexpertly-arranged small press shows. We were always the music source for our corner of the convention hall: RATM in the morning, James Brown in the afternoon, Mozart as the show came to a close. Beer and bad food and 10 people crammed into a hotel double. I loved every second of it.

Every day was a new idea. Every idea was something that someone guaranteed that they would complete. Every guarantee was a limitless promise, even if most of the ideas didn't have limitless promise or anything close to it. We were all in it together and it meant something to all of us. It was our thing and it was about the work (music), man!

Of course, I can only be so cynical and dismissive here because I would gladly turn the clock back 20 years and submerge myself in all of that again. That's why the film appeals to me so much, because I see our time in the expressions of those characters. We loved what we were doing as a supposedly upstart producer, but we yearned to be something bigger, even if we knew that being bigger would take us away from the absolute circus that we all loved and were thoroughly enjoying (and perpetuating.) It was at that time that being creative meant something. It surely didn't mean money, but that didn't matter. It surely didn't mean success, personally or otherwise. It occasionally meant sex, but Jeff was already married, so there were limits (Jeff's wife, Trish, whom I love to death, always kind of endured the studio, rather than engaged in it.) And there was a little fame. A very little. A lifetime of reading comics and a relative mastery of the English language led to me becoming a capable editor (yet one more skill that doesn't help me to land a decent job...) and I have a deep appreciation for and a decent assessment of good art, even if I don't express it that often.

Mostly it was about being with a group of like-minded people who would respond to one person's creative expression not with confusion or disdain, but with honest enthusiasm. We were fans, like Fugit's and Hudson's characters, who had a deeper appreciation for what was being shown to them than most (neither was "on drugs!" to make it a good time, as it were.) And, more than that, we were also the creators. I miss a lot of things about the studio: the people (I've only been able to keep in touch with Jeff and Dave, and then only sparingly), the road trips, the feeling of success when a project made it to print. But most of all I miss the ability to toss out an idea and have people immediately bounce one or two back. I miss bringing up a story idea and having people immediately become enthusiastic, rather than confused or hesitant. I miss walking into a space with Jeff and being able to feel like I was part of something, as I am part of so very little now.

I watch that film and I see us, even if on a much smaller scale. I'd give a lot to do that again.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.