Sunday, March 31, 2013

The storm begins

So, a solid opening episode. As with both previous seasons, there were a lot of intro and catch-up sequences in this first offering. That's going to be standard in a series as complex as this one but the best part about that, of course, is the intro element, since we got to see a few new elements to the story that book readers have been waiting for. A couple of those elements showed up in the title sequence, as Winterfell became largely replaced by the smoking ruin that it now is and Astapor appeared for the first time.

The Wildling sequence was simply a way to introduce Mance Rayder (and Tormund Giantsbane), which is fine, but it was also a great way to display another of the fantasy elements in the northern story by showing a giant for the first time. The key element of this sequence was the clear maturing of Jon Snow, as he properly plays the subterfuge in responding to Mance by using his own outrage at the actions of Craster to fuel his story. Telling a good story often requires a foundation in truth and/or history, as any good author will tell you (even GRRM, who based this tale on the Wars of the Roses and the Italian city-state wars.) I'm glad they kept in the scene of Jon kneeling to Tormund, though.

We're treated to two lengthy sequences of Tyrion, since he was the key player of last season and had the most tumultuous events right near the end. Pod prevents Bronn's attempt at sexposition. It was interesting to note Tyrion and Cersei's rapid descent back into standard sibling rivalry as soon as they began discussing their father. ("What are you going to tell him?" "Why do you care?") It sounded like any pair of siblings I've ever known when trying to manipulate their parents to take their respective side. It was good to see them emphasize Bronn's mercenary nature, as well, to keep the audience from becoming too comfortable with the idea that someone in Kings Landing might be doing something out of genuine altruism ("I don't even know how much I'm paying you now." "Which means you can afford it.") I think I'm going to name a band "Knights are worth double." This theme was continued with the brief appearance of another mercenary type, one Salladhor Saan. I'm betting it will be the last we see of the pirate, since his role in the book is equally brief. It's too bad because Lucian Msamati plays him with a great deal of style and personality ("If you fail, they will burn you. If you succeed, they will burn you.") This scene with Davos and his later one on Dragonstone are both effective in presenting his genuine earnestness and internal conflict in trying to serve Stannis and yet detach them both from Melisandre.

However, one wonders at the later scene with Tyrion and Tywin. It drives home the latter's contempt for his son and the broad injustice and disdain that has encompassed Tyrion's life to date... but we already knew that. Was this scene really necessary other than to have the excellent Charles Dance on camera for a few minutes in the first episode? Certainly, it might have been presented to indicate Tyrion's desire to escape the game and return to the west, but he had just spent most of the last season showing how much he enjoyed the game so, again, I'm not sure this scene did a whole lot for the story. There was one great line, though: "Jugglers and singers require applause. You are a Lannister."

Robb's entry into Harrenhal had me mostly watching Roose Bolton, of course (for non-book readers: Yes, that's a hint.) When they found the piles of dead inside, I expected Bolton to look as unaffected as ever. Instead, Michael McElhatton showed some emotional impact. I don't think McElhatton has been bad in the role, but Bolton is such an unusual figure that I guess I've been expecting more from him. As Jaime said in SoS: "Bolton's silence was a hundred times more threatening than Vargo Hoat's slobbering malevolence." That's a memory of a terrifying figure and McElhatton is... not. On the upside, the costuming is as brilliant as ever, as you could see the brand of the flayed man on the leather doublet over Bolton's armor. It's that kind of detail that really helps make the show what it is. This scene also introduces Qyburn, which is great for the enormous ripples that it foreshadows, but no sign of the other Free Companions, which is a bit discouraging.

OTOH, on the costuming note, Dan Wenioff and D. B. Weiss laughed about the fact that Jorah Mormont has been wearing the same shirt since season 1 in one of their commentaries on the season 2 DVDs and here he is again in that same yellow shirt. But that's a very minor point of a solid scene with the dragons (Dragonfishing, FTW!), now as large as the average Doberman, and the continued emphasis on Dany's intent to do things "the right way". It wouldn't be too much of a stretch to be cynical about that effort, assuming that Dany being the "good" aspirant to the throne is a bit too convenient (and, of course, is one of the reasons for the long delay of Dance of Dragons (the famed Meereenese knot.)) I'm not there yet, as Dany is still a decently complex character, but I wonder how much they'll choose to focus on that issue in the TV series.

The short scenes with Sansa, showing her maturation into an understanding of how to deal with Littlefinger even as she insists on Shae playing the imagination game properly, and Cersei's subtle conflict with Joffrey, as Margaery becomes the new woman in his life, are well-written developments demonstrating the change of emotion for both. Sansa still wants to imagine herself elsewhere like a child, but adapts outwardly. Cersei wants to resume her control of her son now that war is not at their doorstep, but he's more eager to impress his new bride ("My mother has always had a penchant for drama. Her command of the facts grows less as she grows older.") Cersei, as always, is not above tossing a shot when the opening is presented ("We can't all have a king's bravery.") This is good groundwork for Margaery's role as the frustrating populist and her attempt to sway the people around the capital to side with her (not to mention next episode's arrival of the Queen of Thorns.)

Dany's issues come into sharp focus as she attempts to purchase some Unsullied and later survives an assassination attempt. Unfortunately, the latter was attempted by a Sorrowful Man in the books and is replaced by the Qartheen warlocks here. Given that Jaqen H'ghar kept going on about the Red God and didn't bring up the Faceless Men, does that mean that both groups will be absent in the show? Part of what makes the world real is the high number of groups, factions, people, and motivations. Continuing the House of the Undying story seems to detract from the fact that many people want to see Dany dead for any number of reasons. And, of course, they had to do the arrival of Barristan Selmy in the open, as there's not much chance of fooling the audience by calling him "Whitebeard" for a few thousand pages. Even so, where was Strong Belwas?! Is he another detail to be brushed aside? They've already eliminated a number of characters from Dany's story (including her handmaidens.) I understand the limits of budget (you can only pay so many actors) and time (and have them on screen) but turning the whole thing into the Dany and Jorah show doesn't really serve the texture of the story, either.

Still, a solid opening and one has to be prepared for the deviations from the books, as both the showrunners have warned about them. It's good to be back.

Friday, March 15, 2013

Songs to shag to

Horrible prepositional phrases, FTW!

There's very little possible argument against music as a sexual force. It's been condemned throughout history as an enabler, from David to Marilyn (no, not that Marilyn (thanks, Brian) but, yeah... her, too.) What's occasionally rattled around in my brain (and... other... places...) is what kind of music really drives the sexual impulse. It certainly depends on the listener(s) and their particular tastes and impulses, but sometimes it's the foundation of the track:

Ministry's Jesus Built My Hotrod off their transcendent Psalm 69 can't be described any other way by anyone willing to pay attention. Gibby Haynes' obvious lyrics and the song's driving, repetitive beat tend to make it obvious. But would it be a song that encourages sex with someone other than oneself?

Schubert's Ave Maria, on the other hand, is a piece I've heard recommended more than once to "set and continue the mood."

I can see the possibilities, even if it's something that might not occur to me. I wonder, however, if the soprano's presence is too much of an intrusion into the situation for most people. Does she make one rise and fall with her voice or propel one forward? Of course, in the classical vein, many people say you can't go wrong with the classic:

The physical mimicry of Ravel's Bolero, shifting from a slow, quiet build with an everconstant beat to something of more prominence is doubtlessly why it's lasted through the years as music emblematic of the deed. In the modern era, its attachment to Bo Derek and the movie 10 has certainly perpetuated that mental image.

Or we can shift away from mimicry and return to the direct approach:

John Lee Hooker's I'm in the Mood is not only a song explicitly about sex, but also contains that languid beat that tugs at your guts until you're willing to move in the way he wants you to. Many people think that there's something essentially sexual about the blues and its origins from long, slow, hot nights along the Mississippi. Of course, if you'd rather stick with modern tradition, you hearken back to the 70s:

I'd never be able to do it because I grew up in the 70s and Barry White makes me think of seedy, vaguely-Irish-themed bars, filled with smoke and the sounds of Space Invaders; not that the increasingly rapid and regular rhythm of the advancing aliens doesn't make a good aural simulation.

But there's a key element: Is the music supposed to draw you into another world or help enhance the one you're in? I suppose it depends on whom you have to imagine you're screwing, if you have to do that, but then we wouldn't really be talking about playing the right music. Personally, I remember having one of the more thrilling experiences of my life while listening to

AC/DC's Shake a Leg. Again, it was the driving beat and urgency of the whole track (I will forever be rooted in punk, I think) that kind of set the tone for the whole moment. We had put the album on to cover the noise and, thankfully, this track came on at just the right time, just as things were reaching a physical crescendo, as it were. Just like Ministry, it's a complete separation from the slower and just as intense urges driven by players like Hooker and again highlights the question of just which world you're trying to inhabit at any given moment.

Of course, sometimes it's all about timing. I have a friend who was hitting his peak right around the time that someone next door in the dorm was blasting Kraftwerk at 11:

He said that he could never hear this track again without, um, feeling it. Of course, some would say that techno/house/dub music like The Orb's Blue Room

is supposed to inspire precisely that kind of motion on the dance floor, vertically and horizontally. I can't really disagree with that, especially given the ethereal quality that is, in fact, meant to transport the listener (often to another world...) I had this track playing in a hotel room in Coldwater, MI one time (long story.)

Admittedly, I had sexual meaning on the brain tonight after tripping over Friends With Benefits while looking for a brief distraction. I like Mila Kunis as an actress (and, because, well, yeah) and I think the chemistry of the two stars and the script were both great but it was, in the end, yet another formulaic romantic comedy that spoiled all of that potential by kowtowing to test audiences. They were "daring" enough to make the movie largely about sex (trying to PG-13 it would have sacrificed the essential tenet of the story) but music and sex will always beat movies and sex, outside of the whole pr0n thing (Oh. That.) because the former often requires actual thought, whereas the latter frequently avoids it.

There's very little possible argument against music as a sexual force. It's been condemned throughout history as an enabler, from David to Marilyn (no, not that Marilyn (thanks, Brian) but, yeah... her, too.) What's occasionally rattled around in my brain (and... other... places...) is what kind of music really drives the sexual impulse. It certainly depends on the listener(s) and their particular tastes and impulses, but sometimes it's the foundation of the track:

Ministry's Jesus Built My Hotrod off their transcendent Psalm 69 can't be described any other way by anyone willing to pay attention. Gibby Haynes' obvious lyrics and the song's driving, repetitive beat tend to make it obvious. But would it be a song that encourages sex with someone other than oneself?

Schubert's Ave Maria, on the other hand, is a piece I've heard recommended more than once to "set and continue the mood."

I can see the possibilities, even if it's something that might not occur to me. I wonder, however, if the soprano's presence is too much of an intrusion into the situation for most people. Does she make one rise and fall with her voice or propel one forward? Of course, in the classical vein, many people say you can't go wrong with the classic:

The physical mimicry of Ravel's Bolero, shifting from a slow, quiet build with an everconstant beat to something of more prominence is doubtlessly why it's lasted through the years as music emblematic of the deed. In the modern era, its attachment to Bo Derek and the movie 10 has certainly perpetuated that mental image.

Or we can shift away from mimicry and return to the direct approach:

John Lee Hooker's I'm in the Mood is not only a song explicitly about sex, but also contains that languid beat that tugs at your guts until you're willing to move in the way he wants you to. Many people think that there's something essentially sexual about the blues and its origins from long, slow, hot nights along the Mississippi. Of course, if you'd rather stick with modern tradition, you hearken back to the 70s:

I'd never be able to do it because I grew up in the 70s and Barry White makes me think of seedy, vaguely-Irish-themed bars, filled with smoke and the sounds of Space Invaders; not that the increasingly rapid and regular rhythm of the advancing aliens doesn't make a good aural simulation.

But there's a key element: Is the music supposed to draw you into another world or help enhance the one you're in? I suppose it depends on whom you have to imagine you're screwing, if you have to do that, but then we wouldn't really be talking about playing the right music. Personally, I remember having one of the more thrilling experiences of my life while listening to

AC/DC's Shake a Leg. Again, it was the driving beat and urgency of the whole track (I will forever be rooted in punk, I think) that kind of set the tone for the whole moment. We had put the album on to cover the noise and, thankfully, this track came on at just the right time, just as things were reaching a physical crescendo, as it were. Just like Ministry, it's a complete separation from the slower and just as intense urges driven by players like Hooker and again highlights the question of just which world you're trying to inhabit at any given moment.

Of course, sometimes it's all about timing. I have a friend who was hitting his peak right around the time that someone next door in the dorm was blasting Kraftwerk at 11:

He said that he could never hear this track again without, um, feeling it. Of course, some would say that techno/house/dub music like The Orb's Blue Room

is supposed to inspire precisely that kind of motion on the dance floor, vertically and horizontally. I can't really disagree with that, especially given the ethereal quality that is, in fact, meant to transport the listener (often to another world...) I had this track playing in a hotel room in Coldwater, MI one time (long story.)

Admittedly, I had sexual meaning on the brain tonight after tripping over Friends With Benefits while looking for a brief distraction. I like Mila Kunis as an actress (and, because, well, yeah) and I think the chemistry of the two stars and the script were both great but it was, in the end, yet another formulaic romantic comedy that spoiled all of that potential by kowtowing to test audiences. They were "daring" enough to make the movie largely about sex (trying to PG-13 it would have sacrificed the essential tenet of the story) but music and sex will always beat movies and sex, outside of the whole pr0n thing (Oh. That.) because the former often requires actual thought, whereas the latter frequently avoids it.

Sunday, March 3, 2013

Finally, the deeper meaning

Significant spoilers below if you haven't seen the most recent episode of The Walking Dead.

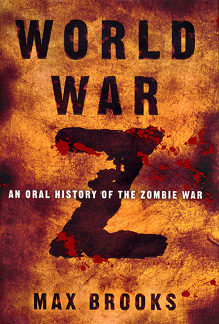

I'm not a huge zombie fan. Most of the entertainment surrounding them is pretty one-note: dead people chase, live people flee and occasionally kill. None of the Living Dead films has ever been more complex than that and most have been relatively self-contained in scope, aside from occasional details about what might be happening elsewhere. The whole world is represented by one little town or even one shopping mall. The exceptions to that are the "28" films (Days and Weeks), which examined the initiation of the problem from a purely scientific perspective (a weaponized disease that escaped containment) and which instigated the utter collapse of the British nation, and World War Z, an excellent book presented as a series of first-hand accounts collected by a UN Commission ten years after the "zombie war".

The book is used to examine any number of social issues that confront us today and which would be accentuated by the utter breakdown of society that takes place during the war, just as it does in the 28 films. That is what makes both book and films interesting, because the problems are far more complex than simply confronting walking corpses. The Walking Dead, originally as a comic and now as the TV series, is presented in a similar vein: the story isn't about running from and occasionally killing zombies. It's about what happens when society completely breaks down. Where does food come from? Where does electricity come from? Who enforces the laws? Who heeds them? Do you absorb others into your group, creating security but also creating more mouths to feed? Or do you reject all but a chosen few once you've learned to trust them?

The TV series has come under criticism from fans of the Romero movies who profess to simply want more scenes of hardcore corpse-killing action. That's a series that would last about two seasons and then get cancelled and the producers and the original writer of the story, Robert Kirkman, have often tried to explain that reality. There has to be something more to the story being presented or else it will quickly become trite. Tonight's episode highlighted that in almost every way possible and finally made the last two-and-a-half seasons well worth watching.

Lennie James returns as Morgan, who appeared in the first episode of the first season with his son, Duane (Adrian Turner), as they rescue Rick Grimes (Andrew Lincoln) after his escape from the hospital. They're holed up in their house in Rick's home town and they explain how the world has changed before Rick sets off in search of his family, promising to try to keep in touch with them by radio. Tonight, we learned that Morgan has remained in town, but shifted locations to a more defensible area where he's amassed an arsenal and established an array of traps for the walkers while he continues to paint doomsday graffiti on every available surface. Duane has died and turned at the hands of his mother whom Morgan says he was too selfish and too weak to kill. Morgan has been driven at least mildly insane by this course of events and is now determined to embody the nihilistic approach toward the world that he thinks is the only reasonable course: everyone will turn and everyone will die, so there's no sense in associating with other other people or trying to rebuild society.

This is the crux of the story: Will society be rebuilt and, if so, by whom and how? The Governor of Woodbury has one approach that seems bent on authoritarian control and an intent that society will be what they want it to be, which is closer to the approach of most of the forces present in the 28 films. Rick's group, on the other hand, seems relatively deterministic: survival is the only real goal and the future will somehow take care of itself, once the problem of the zombies is resolved, which is closer to World War Z's depiction of the problem. The Walking Dead has managed to incorporate both approaches and this episode is what brings it into focus. Morgan had been a survivor, but now presents as an iconoclast. Nothing matters and it's his own weakness that has assured that situation (again, still somewhat deterministic, as his inaction seemingly assured his insanity and change in philosophy.) As he says: "I was too weak and it's people like me that have inherited the Earth."

Meanwhile, the former iconoclast of Rick's group, Michonne, discovers in the course of the same episode that perhaps it is better to be part of a group than a loner determined to distrust everyone. She does this by assisting Carl in the retrieval of the last picture of his mother that he knows to exist. His effort to reach this is motivated by personal feelings, but also by his desire to show his sister, Judith, what their mother looked like. In this way, he firmly positions himself in the camp of those trying to rebuild society, as he understands that the foundation of many human relations is the memory of what has gone before. If we don't possess knowledge of our forebears, we're cast adrift; essentially making it up as we go along, rather than confronting problems with a set of values rooted in the past and our knowledge of the people that lived then. As Orwell said: "Those who control the past, control the future. Those who control the present, control the past." That's a bit more heavy-handed than Carl's motivations, but the truth is essentially the same. Society will be based on a vision of what the controllers feel is essential to preserve, whether out of genuine altruism (Carl) or darker motivations (The Governor.)

I've been watching the series because I'm interested in most comic-oriented stories and Kirkman's is one that has been spoken of quite highly (I only read the first arc.) At times, it was difficult to continue because the story seemed to lack purpose. It was, in fact, just a bunch of people sitting around bemoaning their fate and occasionally entertaining us with new methods of killing walkers. But the third season has been a bit of a revelation in that it finally began to address the bigger picture and this episode brought it home, not because it delivered some poorly-executed expositional homily to the idea of recreating what was, but because it showed people confronting those problems and how it motivates and changes all of them. In that respect, I think I've become an actual fan.

I'm not a huge zombie fan. Most of the entertainment surrounding them is pretty one-note: dead people chase, live people flee and occasionally kill. None of the Living Dead films has ever been more complex than that and most have been relatively self-contained in scope, aside from occasional details about what might be happening elsewhere. The whole world is represented by one little town or even one shopping mall. The exceptions to that are the "28" films (Days and Weeks), which examined the initiation of the problem from a purely scientific perspective (a weaponized disease that escaped containment) and which instigated the utter collapse of the British nation, and World War Z, an excellent book presented as a series of first-hand accounts collected by a UN Commission ten years after the "zombie war".

The book is used to examine any number of social issues that confront us today and which would be accentuated by the utter breakdown of society that takes place during the war, just as it does in the 28 films. That is what makes both book and films interesting, because the problems are far more complex than simply confronting walking corpses. The Walking Dead, originally as a comic and now as the TV series, is presented in a similar vein: the story isn't about running from and occasionally killing zombies. It's about what happens when society completely breaks down. Where does food come from? Where does electricity come from? Who enforces the laws? Who heeds them? Do you absorb others into your group, creating security but also creating more mouths to feed? Or do you reject all but a chosen few once you've learned to trust them?

The TV series has come under criticism from fans of the Romero movies who profess to simply want more scenes of hardcore corpse-killing action. That's a series that would last about two seasons and then get cancelled and the producers and the original writer of the story, Robert Kirkman, have often tried to explain that reality. There has to be something more to the story being presented or else it will quickly become trite. Tonight's episode highlighted that in almost every way possible and finally made the last two-and-a-half seasons well worth watching.

Lennie James returns as Morgan, who appeared in the first episode of the first season with his son, Duane (Adrian Turner), as they rescue Rick Grimes (Andrew Lincoln) after his escape from the hospital. They're holed up in their house in Rick's home town and they explain how the world has changed before Rick sets off in search of his family, promising to try to keep in touch with them by radio. Tonight, we learned that Morgan has remained in town, but shifted locations to a more defensible area where he's amassed an arsenal and established an array of traps for the walkers while he continues to paint doomsday graffiti on every available surface. Duane has died and turned at the hands of his mother whom Morgan says he was too selfish and too weak to kill. Morgan has been driven at least mildly insane by this course of events and is now determined to embody the nihilistic approach toward the world that he thinks is the only reasonable course: everyone will turn and everyone will die, so there's no sense in associating with other other people or trying to rebuild society.

This is the crux of the story: Will society be rebuilt and, if so, by whom and how? The Governor of Woodbury has one approach that seems bent on authoritarian control and an intent that society will be what they want it to be, which is closer to the approach of most of the forces present in the 28 films. Rick's group, on the other hand, seems relatively deterministic: survival is the only real goal and the future will somehow take care of itself, once the problem of the zombies is resolved, which is closer to World War Z's depiction of the problem. The Walking Dead has managed to incorporate both approaches and this episode is what brings it into focus. Morgan had been a survivor, but now presents as an iconoclast. Nothing matters and it's his own weakness that has assured that situation (again, still somewhat deterministic, as his inaction seemingly assured his insanity and change in philosophy.) As he says: "I was too weak and it's people like me that have inherited the Earth."

Meanwhile, the former iconoclast of Rick's group, Michonne, discovers in the course of the same episode that perhaps it is better to be part of a group than a loner determined to distrust everyone. She does this by assisting Carl in the retrieval of the last picture of his mother that he knows to exist. His effort to reach this is motivated by personal feelings, but also by his desire to show his sister, Judith, what their mother looked like. In this way, he firmly positions himself in the camp of those trying to rebuild society, as he understands that the foundation of many human relations is the memory of what has gone before. If we don't possess knowledge of our forebears, we're cast adrift; essentially making it up as we go along, rather than confronting problems with a set of values rooted in the past and our knowledge of the people that lived then. As Orwell said: "Those who control the past, control the future. Those who control the present, control the past." That's a bit more heavy-handed than Carl's motivations, but the truth is essentially the same. Society will be based on a vision of what the controllers feel is essential to preserve, whether out of genuine altruism (Carl) or darker motivations (The Governor.)

I've been watching the series because I'm interested in most comic-oriented stories and Kirkman's is one that has been spoken of quite highly (I only read the first arc.) At times, it was difficult to continue because the story seemed to lack purpose. It was, in fact, just a bunch of people sitting around bemoaning their fate and occasionally entertaining us with new methods of killing walkers. But the third season has been a bit of a revelation in that it finally began to address the bigger picture and this episode brought it home, not because it delivered some poorly-executed expositional homily to the idea of recreating what was, but because it showed people confronting those problems and how it motivates and changes all of them. In that respect, I think I've become an actual fan.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)