Significant spoilers below if you haven't seen the most recent episode of The Walking Dead.

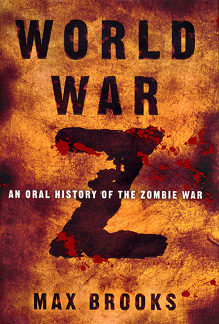

I'm not a huge zombie fan. Most of the entertainment surrounding them is pretty one-note: dead people chase, live people flee and occasionally kill. None of the Living Dead films has ever been more complex than that and most have been relatively self-contained in scope, aside from occasional details about what might be happening elsewhere. The whole world is represented by one little town or even one shopping mall. The exceptions to that are the "28" films (Days and Weeks), which examined the initiation of the problem from a purely scientific perspective (a weaponized disease that escaped containment) and which instigated the utter collapse of the British nation, and World War Z, an excellent book presented as a series of first-hand accounts collected by a UN Commission ten years after the "zombie war".

The book is used to examine any number of social issues that confront us today and which would be accentuated by the utter breakdown of society that takes place during the war, just as it does in the 28 films. That is what makes both book and films interesting, because the problems are far more complex than simply confronting walking corpses. The Walking Dead, originally as a comic and now as the TV series, is presented in a similar vein: the story isn't about running from and occasionally killing zombies. It's about what happens when society completely breaks down. Where does food come from? Where does electricity come from? Who enforces the laws? Who heeds them? Do you absorb others into your group, creating security but also creating more mouths to feed? Or do you reject all but a chosen few once you've learned to trust them?

The TV series has come under criticism from fans of the Romero movies who profess to simply want more scenes of hardcore corpse-killing action. That's a series that would last about two seasons and then get cancelled and the producers and the original writer of the story, Robert Kirkman, have often tried to explain that reality. There has to be something more to the story being presented or else it will quickly become trite. Tonight's episode highlighted that in almost every way possible and finally made the last two-and-a-half seasons well worth watching.

Lennie James returns as Morgan, who appeared in the first episode of the first season with his son, Duane (Adrian Turner), as they rescue Rick Grimes (Andrew Lincoln) after his escape from the hospital. They're holed up in their house in Rick's home town and they explain how the world has changed before Rick sets off in search of his family, promising to try to keep in touch with them by radio. Tonight, we learned that Morgan has remained in town, but shifted locations to a more defensible area where he's amassed an arsenal and established an array of traps for the walkers while he continues to paint doomsday graffiti on every available surface. Duane has died and turned at the hands of his mother whom Morgan says he was too selfish and too weak to kill. Morgan has been driven at least mildly insane by this course of events and is now determined to embody the nihilistic approach toward the world that he thinks is the only reasonable course: everyone will turn and everyone will die, so there's no sense in associating with other other people or trying to rebuild society.

This is the crux of the story: Will society be rebuilt and, if so, by whom and how? The Governor of Woodbury has one approach that seems bent on authoritarian control and an intent that society will be what they want it to be, which is closer to the approach of most of the forces present in the 28 films. Rick's group, on the other hand, seems relatively deterministic: survival is the only real goal and the future will somehow take care of itself, once the problem of the zombies is resolved, which is closer to World War Z's depiction of the problem. The Walking Dead has managed to incorporate both approaches and this episode is what brings it into focus. Morgan had been a survivor, but now presents as an iconoclast. Nothing matters and it's his own weakness that has assured that situation (again, still somewhat deterministic, as his inaction seemingly assured his insanity and change in philosophy.) As he says: "I was too weak and it's people like me that have inherited the Earth."

Meanwhile, the former iconoclast of Rick's group, Michonne, discovers in the course of the same episode that perhaps it is better to be part of a group than a loner determined to distrust everyone. She does this by assisting Carl in the retrieval of the last picture of his mother that he knows to exist. His effort to reach this is motivated by personal feelings, but also by his desire to show his sister, Judith, what their mother looked like. In this way, he firmly positions himself in the camp of those trying to rebuild society, as he understands that the foundation of many human relations is the memory of what has gone before. If we don't possess knowledge of our forebears, we're cast adrift; essentially making it up as we go along, rather than confronting problems with a set of values rooted in the past and our knowledge of the people that lived then. As Orwell said: "Those who control the past, control the future. Those who control the present, control the past." That's a bit more heavy-handed than Carl's motivations, but the truth is essentially the same. Society will be based on a vision of what the controllers feel is essential to preserve, whether out of genuine altruism (Carl) or darker motivations (The Governor.)

I've been watching the series because I'm interested in most comic-oriented stories and Kirkman's is one that has been spoken of quite highly (I only read the first arc.) At times, it was difficult to continue because the story seemed to lack purpose. It was, in fact, just a bunch of people sitting around bemoaning their fate and occasionally entertaining us with new methods of killing walkers. But the third season has been a bit of a revelation in that it finally began to address the bigger picture and this episode brought it home, not because it delivered some poorly-executed expositional homily to the idea of recreating what was, but because it showed people confronting those problems and how it motivates and changes all of them. In that respect, I think I've become an actual fan.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.