Monday, December 17, 2018

Emotional tools

Alfonso Cuarón stated that he wanted to make his latest film, Roma, 12 years ago, right after he made the highly-regarded Children of Men. But he also said that he now feels it was a good thing that he didn't do that, since he lacked the "emotional tools" to tell the story properly. Given that Roma is a story based on those emotional tools that all of us use in daily life, I think he may have been correct in both doing and saying so.

Roma is a story told from the perspective of Cleo, a cleaning woman in a well-to-do household in Mexico City in 1970. The story is semi-autobiographical, as Cuarón grew up in the Roma neighborhood of that city and wanted to convey something about his childhood there. It becomes quickly apparent that the youngest of the four children, Pepe, is the stand-in for the director as he spends most of his time observing what is happening and spending time getting Cleo's feedback on events in the household; just as Cuarón did in preparing for the film, through extensive conversations with his own childhood housekeeper. The traumas that engulf Cleo and the members of her family (as this is clearly what they are) are not exotic or complicated in a storytelling sense, but they carry the complexity that emotional situations of this kind always have. So, in a sense, Roma is not complicated, but it carries great emotional depth because it's something that is both instantly relatable for many people and still foreign enough (leaving aside the dual subtitles; Spanish and Mixteca) to hold one's interest. Cuarón emphasizes that simplicity with the opening shot of the film over which the credits are depicted, which is nothing but the tile of the driveway, occasionally broken by water and soap suds, which we later discover is Cleo cleaning dog shit off that driveway. But it's that simple take on an everyday task that becomes entrancing when contrasted with the dense emotional interplay of the characters.

The film is also a woman-focused story, in that men are largely absent other than a couple of key moments, while everyone else deals with the impact of those moments or the impact of their absence afterwards. Fermin, Cleo's boyfriend, we eventually learn is a member of Los Halcones (from the Corpus Christi massacre), a paramilitary group trained by the government (and funded by the CIA) to react to student demonstrations. He impregnates and then abandons her before later reappearing in the midst of one of those demonstrations with severe consequences on whether she can have that baby. Antonio, the father (figure) of the family, whose most notable contribution to it is the Galaxie which can barely fit into their driveway, later abandons both car and family, leaving all of them to deal with the repercussions. Indeed, Antonio is so much an afterthought in the film that we never a closeup on his face or even see it for longer than a split second. Again, these aren't complicated storylines. The plot is not dense. The beauty of the film comes across in how simply it's told, with Cuarón's love of long shots (the opening, Cleo sitting in the theater waiting for Fermin to return, staring at the bumper of the Galaxie while Antonio tries to maneuver it inside) and stark imagery keeping the viewer paying attention to the most detailed things provided to them: the characters' faces and the emotions flowing across them. The decision to shoot it in digital black-and-white maintains that simple and spartan approach to the vision that the director wanted to convey.

There's been some debate about whether the "appropriate" venue in which to screen the film is in a theater or at home on Netflix. Cuarón, as one might expect, chimed in with his opinion at a recent event that Roma is best viewed in a theater. I think that's probably based on the mindset he wants his audience to have. In a darkened theater, there are no other distractions, visual or otherwise, and you experience the film the way he does: as memory, quietly, intimately. We ended up watching it on Netflix and perhaps that's why, despite its obvious high points, I found myself less impacted by it than I had anticipated. As noted many times before, I'm a story guy. I want you to tell me a story that holds my interest. I think Cuarón does that, but it's not a story that sat with me or had me mulling it over days later. I was entertained by it. I was fascinated, as usual, by the craft which he demonstrates in all of his films. But I found it far less earth-shattering than many other people have. I can definitely recommend carving a couple hours out of your life to sit in front of it, wherever you do so, and would be interested to hear others' experience from seeing it in theaters. But it's not a film that I would urge people not to miss. As much as I enjoyed the story, it's like many others out there.

Monday, November 12, 2018

True believer

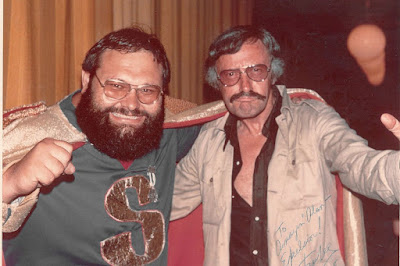

I had a complicated relationship with Stan Lee, who died today at the age of 95. Even as a kid, I knew that his exuberant cheerleading for the Marvel Way was something that everyone around him would roll their eyes at. I had figured out the inside joke that was the No Prize and knew that his favorite buzzword "Excelsior!" was just his way of being bombastic at the same time as he was exercising his vocabulary (a habit I picked up from him and am still prone to.) If we'd actually had a relationship, Stan would have been the weird uncle that everyone laughed with (or at) but actually didn't mind having around for Thanksgiving.

As into the comic world as I was, I also knew that as much as Stan seemed to be the godfather of Marvel Comics, Jack Kirby had also been just as influential in the creation of the Marvel universe and most of the key characters that inhabited it: the Fantastic Four, the Hulk, Thor, Iron Man, the X-Men, the Inhumans, Black Panther, Galactus, and the character that would go on to become Lee's favorite and exclusive writing property for many years: the Silver Surfer. Kirby became the comics creators' favorite upon his death, as it became popular to draw a comparison between Kirby's departure from Marvel and that of Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster (the creators of Superman, who had been exiled by DC), especially when the question of creators' rights in a work-for-hire world was raised. Stan, editor-in-chief and soon publisher at Marvel, was dismissed as the huckster, while Kirby was the genius. As much respect as I had and still have for Kirby, I felt badly for Stan that he had been relegated to the role inhabited by so many of us, the secondary people in comics: the writers. The way their relationship was often presented was that Kirby was the real creative force and Lee simply animated the characters; as if Kirby created the puppets and wrote the script and Stan simply flapped his hands in the window to make them come alive.

But the fact is that they did come alive in his hands and as much as Kirby is properly lauded for his remarkable imagination, it was Stan Lee who made The Amazing Spider-Man into Marvel's most popular title, not least by focusing on social issues of the day, such as the Vietnam War and student activism, as well as the personal lives of the characters in the book. It was Stan Lee who created the first African-American superhero when he and Gene Colan created The Falcon in the pages of Captain America. It was Stan Lee who broke the back of the execrable Comics Code Authority, by insisting that his story about Harry Osborn's drug addiction be published without the CCA seal, proving that the censor was outdated and served no purpose for the more mature readers of modern comics. Goofy uncle that he was, Stan's social consciousness resonated with me and I felt that he saw the world the same way I did; those dark eyes glistening from his mop-haired, pornstached caricature on the Stan's Soapbox page. Take heart, true believers!, he said. And I did, because I knew that he was one, too. He believed that stories could change people's outlook on the world, even if those stories were full of colorful costumes and onomatopoeic sound effects. I could feel the stress of someone trying to go to school, hold down a job, and protect the streets of New York at the same time. I could wonder over the anguish of a man who could lead his people without being able to utter a word. I could imagine the pathos of a being who had been responsible for guiding a force of nature to the deaths of billions. I could feel these characters and these stories and knew that I wanted to do something like that.

Stan was later levered away from being the face of the company to essentially being its mascot. He was, again, the weird uncle kind of shuffled off to the side, still cheerleading, but no longer leading. Comics were a serious business now, worth real money, and stockholders and corporate boards were the ones who owned the soapbox. But I'll never forget sitting down in a room with Stan and a couple dozen other people at a convention and listening to him tell us stories about how they meant real money back when he helped build the company into the monstrosity it became. That real money was about jobs and paychecks and paying the rent, not only on their homes, but on the building where the studio was housed. He talked about how they would occasionally get letters essentially saying "You guys suck!" and he'd tack them up on the walls because at least they were getting letters, which meant that somewhere, someone was reading. Of course they were, Stan. We read and we never forgot. We always knew who you were.

Thursday, September 6, 2018

The end of cinema (not really...)

Burt Reynolds died today at the age of 82. Reynolds was the first real "movie star" that I was aware of as a kid. I was fortunate enough to see a lot of movies when I was young, including many that most parents would be arrested for taking their kids to these days, so I knew what actors were and was conscious of them moving between films (Richard Dreyfuss was in Jaws and Close Encounters of the Third Kind) and moving between media (Chevy Chase going from Saturday Night Live to Foul Play, for instance.) But Reynolds was the first person I remember being aware of as the centerpiece of whichever movie he was in. It wasn't so much that he was playing a role in a movie, as much as it was that he was Burt Reynolds in that movie. Richard Dreyfuss could be two very different people in two different films, but Burt was always Burt and mostly Burt was Bo "Bandit" Darville, half the namesake of Smokey and the Bandit, the film I first remember becoming aware of him as said "movie star."

I would soon see his earlier stuff like Deliverance and The Longest Yard and his later stuff like Sharky's Machine and Stick, where he played much more serious, always brooding roles. He did that really well and Deliverance remained one of his most critically-hailed performances. But it was as Bandit or Sonny Hooper (Hooper) or JJ McClure (The Cannonball Run) or Stroker Ace (Stroker Ace) or Jack Rhodes (Rough Cut) that you always knew Burt, because he was the same good ol' boy doing good ol' boy things with that smarmy grin and gravelly voice that gave him all the charm in the world. In that respect, Reynolds was something of a cultural icon, in that he personified the vapid and dilettantish 70s with its garish colors, wide lapels, sense of style over substance, and towering uncertainty economically, politically, and socially; only to fade somewhat in the more mercantile and crime-oriented 80s, with the suffusion of culture with the concepts of Wall Street, machine intelligence, and success determined only by one's bank balance; until he saw everything come crashing to earth as the 90s moved on without him and his bankruptcy, only to look back on his highlight decade with some fondness and a great deal of interest in his other hailed role as Jack Horner in Boogie Nights. Appropriately, his character is a person who doesn't want to accept the fact that the world does move forward, resisting the change in the porn market from proper films that an auteur could still claim pride in to video that could be sold on any street corner.

Unfortunately, that transition kind of predicted the end of his career, in that his last noted performance was in an otherwise poor film called The Last Movie Star, where an embittered older actor deals with the fading of his glory days. Many projects he worked on in his last years were direct-to-DVD, just like Jack Horner's films, and a format that itself has faded from the cutting edge of technology and preference. I remember that bitterness emerging even after Boogie Nights, when he had stepped back into the limelight. He was too old to be Bandit any longer and the smarmy grin (and high-pitched Bandit laugh) had faded to something more genial; the frustrated mentor who doesn't want to be doling out advice on how to take action or direction. He wants to be in there living it, but he'll still be as charming as he has to be while the lips press together, the nostrils flare, and you imagine the smoke pouring from his ears.

I don't look back on that period with any degree of nostalgia. I don't think that the 70s were some kind of elevated period that anyone should want to return to, for any number of reasons. In fact, when I think of films other than Smokey and the Bandit that involved Reynolds, I usually think of his hard-bitten action period exploits, like Stick. Despite my affection for the Bandit, I remember the brooding Reynolds when I think about character models or story atmospheres. Maybe it's the chintzy nature of many of those 70s/early 80s productions or the threadbare plots that were obviously just vehicles (sometimes literally) for Bandit to run around and have a good time. That's not to say that plots or performances in things like Sharky's Machine were any better, but there was something more secure in the idea that not everyone was just having fun all the time. Nevertheless, the image of Burt in my head is still that of Bandit and probably always will be; maybe because I want to be that charming guy just having fun, but know that that's not how things usually work out. That's the life of the movie star when, all along, I feel like Reynolds really wanted to be a "film star"; someone taken as seriously as Marlon Brando, an actual star that Reynolds was once told he resembled too closely to be cast in his first major film (Sayonara.)

I think what I'll look back on most fondly is the fact that, even in those "good ol' boy" movies like Smokey and the Bandit, Reynolds still carried that gravitas that permeated his notable roles like Deliverance.

He was just having fun. But he was doing so with a real awareness of the world around him and how it worked. That's something else that one could attach to that era of uncertainty: people still knew who was fun to hang out with, especially when he was the one who could make you feel alive (or at least well-stocked with beer.)

Sunday, August 26, 2018

Limits testing

[This one is obviously very late. Life and schedules and ambition kind of conspired against me. Episode 4 should be much more timely.]

What we hide from people is often just as important as what we say. Similarly, what we're willing to do is often equally as important as what we're not willing to do. Episode 3 of this season was all about those two concepts, as many different characters were asked to find their limits, while Jimmy, for the most part, sailed through it all.

From Ignacio acting out the cover story that has him getting shot and operated on by a veterinarian in a Jiffy Lube (patiently hovered over by the cousins) to Mike simply turning down a B&E for a rare figurine, these are the decisions that shape these characters, not only for the audience, but the sake of the character's identity. Ignacio, disenchanted as he is with the drug scene, is now serving two masters, either of whom will kill him at a moment's notice if they feel he's a liability. This is the tragic case of someone forced to test his limits for a world that he no longer wants to inhabit; to give in the utmost for a cause that he not only does not believe in, but actively detests.

And then there's Mike, who's not only obviously disappointed that Jimmy would approach him with something so pedestrian, something which doesn't test his abilities at all, but is also clearly disappointed that Jimmy would sink so low as a simple robbery in order to make money. Mike knows that Jimmy is capable of more and so does Jimmy, inherently, but circumstances have put the latter in a situation where immediate cash flow seems more important than the style with which it is delivered. Mike, OTOH, has no such issues and can now pick and choose jobs that suit him. Even so, it's highly likely that Mike would never have bothered to risk himself in a job so simple and with so little payoff.

But Kim is the one we should be paying most attention to, because she ends up seeing both ends of the spectrum in this respect. Her rewrite of what we assume was Chuck's scathing departure letter into a tepid encouragement shows just what she's willing to do to try to salve the wound that Jimmy is feeling and not drive him further into the pit of guilt, despite the fact that he earned it in some respects. When she dissolves into tears, we're left uncertain as to whether it's about her own sense of guilt for having deceived him or the angst over the fact that the letter she wrote couldn't help him without giving away the lie and so simply leaves him in a state that's not worse, but still not good.

On the other end is the meeting with the CEO of Mesa Verde. No small bank suddenly expands into a half-dozen more branches (and elaborately-styled ones, at that) without something happening off the books. She wanders around the display room, knowing that she's gotten herself into something that's going to violate her ethics as surely as what she's just done to Jimmy and has done with him before. Like Ignacio, she's uncomfortable with that, so now comes the test: How far are you willing to go?

The one exception to this overall theme is presented by the return of Gale Botticher. Gale, in his usual constantly positive and endlessly inquisitive way, wants to do more for Gus than the latter actually wants. He's disappointed with the quality of what Gus is working with now and wants to show him a way to do it better. There is no question of willingness of Gale's part, which was always the case in Breaking Bad, as well, which is what made him part of one of the best moments of that show, when Jesse was pushed past his limits and almost broke from Walt completely. On the one hand, it's amusing to see Gale make his return. OTOH, knowing that the most emotionally poignant moments of the character's existence are the ones we've already scene and which won't be a part of Better Call Saul is mildly disappointing.

Episode 3 was a bit of a step back from the majesty of episode 2, but they can't all be park-clearing winners. Plus, this episode managed to lay down a lot more of the interesting themes that will be pursued this season (Nacho's travails, Mesa Verde, Gale, etc.), so there's still plenty to look forward to.

What we hide from people is often just as important as what we say. Similarly, what we're willing to do is often equally as important as what we're not willing to do. Episode 3 of this season was all about those two concepts, as many different characters were asked to find their limits, while Jimmy, for the most part, sailed through it all.

From Ignacio acting out the cover story that has him getting shot and operated on by a veterinarian in a Jiffy Lube (patiently hovered over by the cousins) to Mike simply turning down a B&E for a rare figurine, these are the decisions that shape these characters, not only for the audience, but the sake of the character's identity. Ignacio, disenchanted as he is with the drug scene, is now serving two masters, either of whom will kill him at a moment's notice if they feel he's a liability. This is the tragic case of someone forced to test his limits for a world that he no longer wants to inhabit; to give in the utmost for a cause that he not only does not believe in, but actively detests.

And then there's Mike, who's not only obviously disappointed that Jimmy would approach him with something so pedestrian, something which doesn't test his abilities at all, but is also clearly disappointed that Jimmy would sink so low as a simple robbery in order to make money. Mike knows that Jimmy is capable of more and so does Jimmy, inherently, but circumstances have put the latter in a situation where immediate cash flow seems more important than the style with which it is delivered. Mike, OTOH, has no such issues and can now pick and choose jobs that suit him. Even so, it's highly likely that Mike would never have bothered to risk himself in a job so simple and with so little payoff.

On the other end is the meeting with the CEO of Mesa Verde. No small bank suddenly expands into a half-dozen more branches (and elaborately-styled ones, at that) without something happening off the books. She wanders around the display room, knowing that she's gotten herself into something that's going to violate her ethics as surely as what she's just done to Jimmy and has done with him before. Like Ignacio, she's uncomfortable with that, so now comes the test: How far are you willing to go?

The one exception to this overall theme is presented by the return of Gale Botticher. Gale, in his usual constantly positive and endlessly inquisitive way, wants to do more for Gus than the latter actually wants. He's disappointed with the quality of what Gus is working with now and wants to show him a way to do it better. There is no question of willingness of Gale's part, which was always the case in Breaking Bad, as well, which is what made him part of one of the best moments of that show, when Jesse was pushed past his limits and almost broke from Walt completely. On the one hand, it's amusing to see Gale make his return. OTOH, knowing that the most emotionally poignant moments of the character's existence are the ones we've already scene and which won't be a part of Better Call Saul is mildly disappointing.

Episode 3 was a bit of a step back from the majesty of episode 2, but they can't all be park-clearing winners. Plus, this episode managed to lay down a lot more of the interesting themes that will be pursued this season (Nacho's travails, Mesa Verde, Gale, etc.), so there's still plenty to look forward to.

Monday, August 13, 2018

Creatures of Light and Darkness

For those of you that are New Wave SF nerds like me, you'll recognize the title of one of Roger Zelazny's more esoteric novels. Originally envisioned as simply a writing exercise, Zelazny never intended to publish Creatures of Light and Darkness. But once friend and fellow author, Samuel Delany, heard about it, he encouraged an editor to take the manuscript from Zelazny and put it into print, for good or ill. It has one chapter devoted entirely to poetry and the end is written like a screenplay. In other words, it's a very stylized approach to telling another of Zelazny's stories about futuristic beings of myth and their very human motivations. Similarly, Michelle MacLaren, director of the latest episode of Better Call Saul, used a backlighting technique throughout to indicate moments of tension, where the conflict between characters was subtle but significant to the story; where decisions kept the direction of the story for those characters balanced on that edge between light and darkness that scientists call 'the terminator' as sunlight creeps across the spinning ball of our planet. Would their decisions move them wholly into the light or the darkness or would continue to inhabit the halfway point, not quite sure how or if to proceed?

The first example was Jimmy and Kim, as the former putters around the kitchen, determined to flee from having to talk with Kim about recent events, and to reassure himself that he can still be of value, even without the law license that his now dead brother wrested from him; the only real thing of value that Jimmy has ever acquired in his life. Jimmy's face is shrouded like his soul is and looking away from the light just shows how unwilling he is to face his role in what happened. The next example was Ignacio, who faced his father in darkness, trying to reassure him that the threat from the Salamancas to launder money through his car business was finished, although his father cannot look at his shrouded son. Nevertheless, still fearing for the safety of the son who so wounded him by involving himself with criminals, pays the tax, anyway. Ignacio tries to convince him not to and then surrenders to what he knows he cannot change. The next example was the meeting between Mike and Lydia, as the latter cringes from Mike's bold play at the warehouse, thinking that continuing as normal is better than laying the defense against his inevitable discovery by someone. Mike knows better, but still has to convince the person who effectively outranks him. Here is the former cop, still walking in the twilight with his new partner who covers the drug business contained within the parent corporation; meeting in a darkened conference room, as if someone might discover them with the lights turned on.

The technique is still in evidence when Kim accosts Howard over the backhanded estate settlement that she knows will only further demoralize Jimmy. Their conflict is much more prominent and not subtle, so the contrast is fainter, as Kim's fury lights up the scene. But there's still the faint shadow that symbolizes the undercurrent of Howard wanting to get a last jab in at Jimmy, whom he knows tortured his friend and partner of many years, and Kim, despite her vociferous defense, knowing that Howard is probably justified in wanting to do so. But it comes back in full force in both instances when Gus' men tell him about the results of Hector's tests, as the light streaming through the window in the car and in his office leaves Gus partially in shadow as he struggles with himself and how he should proceed with his attempt to keep Hector alive so that only he can exact the full extent of the vengeance he desires ("I decide what he deserves. No one else.")

There is no shadow in the moment of direct conflict. When Ignacio and Arturo confront Gus' men over the number of kis that they're picking up, everything is brightly lit. The conflict is overt. The threat is real. There is no shadow across it. Everyone knows the motivations at hand and what actions they will drive. But the contrast returns when Arturo is killed and the implications of what Ignacio has done and what he will now have to do are spelled out to him by Gus. As direct as the threat may have been to Arturo, the shadow returns for Ignacio, denying him the assertion that he made to his father about how he was working on getting out of a bad situation, as he is now only that much deeper into darkness with someone who is far more dangerous than Hector.

I've really enjoyed Michelle MacLaren's work over the years on Breaking Bad and Game of Thrones, precisely for her deep understanding of story and how to present it in a visual manner. This may have been her finest effort yet in that respect. It doesn't hurt that Gilligan's writers continue to outdo themselves in presenting the cast with so much red meat to work with. Take Jimmy's interview with Neff Copiers. He knows they'll reject him as unsuitable for a sales job after having been a lawyer, whether it's because of a lack of actual experience or a belief that he'll decide the job is beneath him and they'll have to find someone else when he moves on to another law gig. So he goes back in to convince them that he has what it takes and easily does so. But his own self-loathing; the recognition that that kind of hucksterism is what he's been doing his whole life, prevents him from accepting the job that he wins. All he can think of is how these guys are precisely the kind of marks he's been working since forever and how he won't be able to respect them for giving in so easily to his routine. And, of course, how he can't stand himself at the moment for everything he's done to Chuck and how he doesn't deserve anything good to come his away, especially when it was achieved by Slippin' Jimmy.

Full marks to Rhea Seehorn in this episode. Her scene with Howard was one of her best moments in the entire series, as she ate him alive and confronted him with his own ulterior motives, while she took the opportunity to vent her frustration at the situation that Jimmy still keeps her in. She's doing amazing work and I hope it lands her other solid roles in the future. Similarly, Michael Mando as Ignacio has been getting progressively better as the series has moved along. The emotion on his face when Gus corners him and he realizes just how deep his personal hole has gotten was great. It was extremely entertaining to see Gus doing some of his own dirty work again, too. Other little details, like an appearance by The Cousins at Hector's bedside, and Jimmy and Kim deciding to watch White Heat, a noir film in this most noirish of BCS episodes and a film about a man confessing to a lesser crime to hide a larger one, pushed this one among the best of the series, in my opinion. I was still intrigued by episode one of this season, but episode two has launched BCS back near the top of my TV agenda (right behind Liverpool games.) The series can't get much better, which only makes me want to see how they're going to outdo themselves as we move along.

Thursday, August 9, 2018

Not quite a Klassic

BlacKkKlansman is Spike Lee's latest joint and it was clearly intended as a statement film, rather than a story. There are generally two types of political films: one with a story that delivers a message as part of its theme and one with a message that carries a story. This one is the latter, without doubt, dressed up as it is in the stylistic trappings of a Lee effort that attempts to be the commentary before the critics can get there to extol it.

The best part about its absurdist plot is that it's a true story: the only Black police officer in Colorado Springs did actually infiltrate the Ku Klux Klan and speak with David Duke. But Lee is careful to not let said absurdity override the essential disturbing theme of American racism being alive and well in 1979 and to this very day. All of the direct encounters with the Klan members carry an atmosphere of danger and there are no hi-jinks that would lift the story out of the realm of drama and into comedy. That doesn't mean that the film is a brooding one, as Lee also consciously applied the style of the time in which it's set, using choreography and shooting angles that were an obvious homage to the Blaxploitation films of the 70s (Patrica and Ron skimming toward the camera with guns drawn, etc.) He was also careful to draw tight links to the reality of Trump and his followers in the present day ("There's no way America would ever elect someone like David Duke president!", Topher Grace as Duke muttering about "Making America achieve... greatness again!"), as that part of the message was repeated over and over: In many ways, nothing has changed in the last 40 years and the regular shooting of Black people isn't too far away from the organized lynchings and torture that Harry Belafonte as Jerome Turner spent several minutes elaborating upon for his young revolutionary audience. I think that message is a good one that bears repeating.

My one note of reluctance about the film is that, as has happened with many other Lee joints, I think he was attempting too much with one film and the editing was perhaps hindered by both the amount of material contained in the script (and the message) and the relatively thin characters that weren't able to carry the film from scene to scene. In many ways, it became too obvious that it was a message being delivered and not a story being told. The jumps from scene to scene were often choppy and the pace of the film dragged a bit in the middle, mostly because there wasn't enough story to carry it evenly from act 2 to act 3. You only cared about the inevitable resolution and not enough about what was happening to get you there. There was little warmth in the relationship between Ron (John David Washington) and Patrice (Laura Harrier) and most of the moments when Ron had to deal with the chief or other superiors felt almost as staged as your typical police procedural.

But there were some very strong and memorable moments. I found it kind of fascinating that the few moments of real levity were when Ron was conducting his phone kalls to to Klan members and other cops would be cracking up at his over-the-top performance. Of course, Washington was playing it so straight that what was truly funny about those scenes was watching the other cast members try to restrain themselves and end up giving him away. This is one of the interesting things about comedy, in that some of it can best be enjoyed with other people, so that true enjoyment comes from seeing how other people are reacting, even moreso than anything gained from the actual content of the joke. You'd like to think that that, too, was a part of the message, in that the best way to deal with that kind of visceral and unreasoning hatred and ignorance is to be able to laugh about it (and at the racists) together; taking collective joy in the behavior of fools rather than letting their foibles reduce our own.

Adam Driver as Flip Zimmerman had the most poignant moment of the film when it occurred to him just how much privilege he enjoyed, despite the fact that he was one of the primary unwanteds of the Klan, since it wasn't obvious that he was anything other than a White man. It was a great question of identity when he revealed that being Jewish was never something that was a part of his reality as a child until he grew old enough to understand what it meant and develop his sense of self. But that scene may have been a measure of Driver's greater experience as an actor, since he was able to convey that kind of identity quandary, whereas Washington, as the central figure in all of this, really didn't. He was constantly the straight man in the grand joke. Similarly, it occurred to me in act 3 that the person occupying the typical role of hero in the action scenes was, in fact, Driver, since he was the one taking the physical risks in interacting with the Klan, got the chance to show off his shooting skills, and then finally rescued Stallworth from overzealous cops at the end. So, once again, the person occupying the popularly understood notion of "hero" of the film about Black identity was a White guy (see: Amistad.) And this was a Spike Lee film! Two other performances of real note were Corey Hawkins as Kwame Ture and Jasper Pääkönen as Felix. The latter reminded of no one so much as Michael Biehn as the deranged Lt. Coffey in The Abyss.

Another familiar aspect was the little cultural touches that Lee included, sometimes with a feather, like Mr. Turrentine (Isiah Whitlock) using the tagline ("Sheeeeiiiitttt!") of his most famous role from The Wire, and sometimes with a cinder block, like dropping in the movie posters of those Blaxploitation films while Ron and Patrice are discussing them. I can see the desire to clue people in to what that conversation (and the consequent style touches throughout the film) was about, but I also think the heavy-handed approach kind of diminished the overall effect. No one I saw the film with had seen The Wire, so the Clay Davis moment was lost on them, but sometimes those Easter eggs are things to be discovered with later viewings, rather than shoved in your face the first time. Similarly, while I understand the desire to show the events of Charlottesville from last summer to drive home the fact again that, yes, this is still a reality and these people, including the president, are dangerous and a menace to civil society. But I'm not sure the full footage was as effective as a few still shots with captions would have been, allowing the audience to draw some of their own conclusions, rather than making them for it.

Regardless, it's a film that's well worth seeing for a variety of reasons and probably much more effective in the theater than it will be on smaller screens.

Monday, August 6, 2018

Saul waiting

With the long-awaited release of season 4 tonight, one begins to garner the idea that this may be it for Better Call Saul. Creators Vince Gilligan and Peter Gould have stated that Saul won't exceed the length of its progenitor, Breaking Bad, which means a season 5 would be the limit. However, the opening Cinnabon scenes are possibly finally drawing the noose around Jimmy's existence in Nebraska, with the blankly menacing stares from the cab driver with the 'Albuquerque' air freshener. One could also sense a breaking point at the end, after all the emotional turmoil of Chuck's death, when Jimmy declares that his death is Howard's "cross to bear" when the latter clearly came to Jimmy and Kim seeking sympathy. This is the blame shifting that Jimmy has engaged in throughout his life, but never in such a ruthless manner. There was always the angst apparent in his awareness that he was really doing someone wrong. This time, he's just coasting, likely not least because he's found the angle that lets him off the hook he'd just imagined himself on because of the insurance stunt.

But by that time, we already knew that Jimmy had turned a corner in his emotional transformation. The best moment of the episode was when he and Kim were sitting on the bench outside the ruin of Chuck's house and Jimmy was muttering about how Chuck had been getting better and "something made him relapse." Just watching Rhea Seehorn's face was a treat because so many emotions washed over it in the space of a few seconds it was hard to keep up with all of them. There was the frustration with Jimmy still thinking Chuck could have gotten better; there was the concern for his emotional state; there was the angst over how she was going to get him to change his mind and not blame himself... but there was also the hesitation. That hesitation said that she knew why Chuck had "relapsed" and what may have led to his state of mind that caused the "accident" to happen. She knew because she knows Jimmy. She knows what Jimmy did to Chuck's career and life. She knows how casual Slippin' Jimmy can be about the travails of others. No matter how much she loves Jimmy McGill, there's an inner self to him that's basically amoral. She's been making excuses to herself or simply forgiving him for it up to now, but the crux point may have been reached.

The other clue we might have that this is the final seasons is Bob Odenkirk's statement that "Breaking Bad is going to swallow season 4." With Mike Ehrmantrout well on his way to becoming Gus Fring's fixer and the latter's business now rolling with Hector having been reduced to what will be his wheelchair-bound state, we're rapidly approaching the state of affairs that saw Saul enmeshed in that business as the "criminal lawyer" that Walter White first encountered on behalf of one of his dealers.

Speaking of which, Jonathan Banks continues to excel as Mike. Despite the fact that he ended up doing the "Axel Foley in the bonded warehouse" thing as he was scoping out Madrigal, that whole scene kept us intrigued as we watched him develop an idea of just what kind of front Lydia and Gus were running. You can tell that he's become more comfortable with his return to the twilight of the law, if only by the obvious boredom that he experienced while sitting at home watching the Isotopes, before finally deciding to move on the suspicions he had about the check he received. The music choice for the warehouse bit was also excellent, as was the rest of the episode in that respect. Gilligan's aural cues continue to be a distinct element of his productions and I'm glad that he's not abandoned that trait.

So, this is it. We're in the home stretch of the transformation into the "real pipe-hittin' member of the tribe." Even with the recent and coming deluge of things to watch (Orange is the New Black, second season of Ozark on the 31st, Liverpool, Michigan), I'll still take time to sit down on Monday nights and endure commercials just to see the final pre-chapter of Breaking Bad roll out.

Saturday, July 14, 2018

Not sorry

[Editorial note: I've been spending time away at another site, but decided that the conditions there just weren't appropriate for the writing I'd like to do about TV and cinema (timeliness, image controls, etc.) They, appropriately, really just want to talk about games, so I'm going to start trying to post here about other kinds of media on a twice-weekly basis, be it TV series or movies or whathaveyou.]

Sorry to Bother You, Boots Riley's initial foray into moviemaking, is clearly a project that he's been sitting with for some time. There are details embedded in the story and the production that can provide the careful observer a lot of joy and it's part of what makes the combination alternate reality/urban comedy/morality play a success. The message of the film is both deeply embedded and often parodied at the same time, which brings another arcing theme to the forefront: No matter how crazy things get, you gotta go to work.

The dual message from the very beginning is that capitalism clearly isn't working for a lot of people and the amount of lying that people often have to do in order to participate in that system is ridiculous. We see this from the opening scene, when Cassius Green (Lakeith Stanfield) tries to present a trophy and a plaque indicating what a great employee he was at former jobs that he never had. The joke, however, is on him, because the telemarketing firm he's applying to will hire any warm body off the street. Once he grasps the basic concept of continuing with the Big Lie by adopting his "white voice" to be a successful caller (hearkening back to Dave Chappelle's assertion that "Every Black American is bilingual. We speak street vernacular and we speak job interview."), Cassius begins to climb the socioeconomic ladder at the office, to the point where he's elevated to the level of Power Caller; a title that fairly drips with the multiple meanings of those in society with money being not only able to exercise the greater freedoms that it creates, but having access to the knowledge of how modern society is even uglier than many people imagine. At that point, he has a choice to make: abandon his social ties and the basic morality of standing up for the majority or continue on the path of societally-determined success (i.e. wealth.)

Along the way, Riley continues to present situations and characters that ask a variety of extremely overt and very subtle questions about the state of society and how many lies everyone has to willingly participate in to keep it moving (Gotta go to work...) These range from the most popular show on TV, "I Got the Shit Kicked Out of Me" being displayed as "I Got the S@!# Kicked Out of Me", presenting the fiction that profanity isn't actually in use, to the very basic idea that the only measure of success in modern America is making enough money so that no one else can tell you what to do (reminding one of Office Space's Peter Gibbons' perfect job: "I would do... nothing.") The screenplay is smart enough to take those subtle jabs like the barely concealed profanity and elevate it to something more elaborate. In that case, it would be Mr. _____ (Omari Hardwick), as the guide for Cassius once he makes the coveted level of Power Caller. Mr. _____ is the only other non-white person in the room; thus, his name can't be spoken, as an example of something that is too profane to be revealed, since he serves the overlords (like WorryFree CEO, Steve Lift (Armie Hammer)) both adeptly and very willingly.

But there are a number of smaller creative details that also appear, from the fun with names (Cassius "Cash" Green, Diana DeBauchery) to Danny Glover tossing in his trademark line from 20 years of Lethal Weapon pictures ("I'm too old for this shit.") Riley also gives us comedic bits that demonstrate the characters' awareness of the bizarre reality and falsehoods that they're all living through, such as Anderson (Robert Longstreet) becoming very disturbed about how DeBauchery and Johnny (Michael X. Sommers) are regurgitating the sales/capitalist message that they've absorbed a bit too well to an office full of employees that will be repelled by it; or Cassius easily entering the VIP room at the bar, using the password that never changes and discovering that he's just one more obstacle to be walked over in a room full of regular people aspiring to a higher status, just like he is.

There were some great production approaches. Depicting the world of the telemarketer dropping into the room where their target is answering the phone was a slick depiction of the age of social media, which often brings the realities of those we're interacting with into our most intimate spaces. The setting of Oakland, a city long known for its working resistance to the social order, but now undergoing a rapid course of gentrification, was a great choice. The contrast between Cassius' one room garage apartment, filled with the poorly lit detritus of being lived in, and the starkly white, museum-like apartment with its view of the Oakland city center, was well done. Lift's quip about the "high production values" of the Claymation movie that introduced his Equisapiens program was also a nice study in contrasts; the use of a medium from childhood TV specials introducing a project of grotesquerie maintained the comedic element of this film and made imagining that kind of delivery a feasible choice, even in our own (slightly) more sane world.

Stanfield did an excellent job in the starring role; so much so that certain scenes attempting to depict his struggle with his new life choices seemed superfluous. We didn't need a couple minutes of him explaining how torn he was when that was already splattered across his face every time he faced the camera. This actually contributed to a bit of a slow period in the middle of the film where I found myself almost doing the "hurry up and move on" wave. We don't really need a lengthy conversation between Cassius and Detroit (Tessa Thompson) to know that the former isn't quite on the same awareness page as the latter. Indeed, Thompson's role was kind of disappointing, in that her artistic depiction of what was happening on the streets didn't add a whole lot to the overall story. Similarly, Squeeze (Steven Yeun), as the labor organizer in the office, was kind of pro forma. Yes, Cassius needed someone new to show him the realities of labor-management action and politics, but Squeeze didn't serve much purpose other than to provide the rather obvious romantic complication.

And that's my one real complaint with the film: the messages occasionally felt too obvious and shaped to provide an easy transition between the second and third acts. We didn't need to be hit over the head quite so hard (with a cola can or not) with the impact of these changes on Cassius. Similarly, we didn't really need the happy ending where he ended up getting the girl (back.) Thankfully, there is a little moment at the end that brings the air of bleakness and the bizarre back to something that was edging toward the formulaic, but I think Riley could have gone even farther in keeping things on the fringes of sanity and still gotten the positive audience reaction that studios lust after.

Regardless, it's definitely a worthwhile film that occasionally hits one squarely between the eyes when considering modern America and its, uh, excesses of all kinds. As Riley noted in an interview, the current political situation made some parts of the script a bit too "on the nose". Something to think about when we all head back to work...

Sorry to Bother You, Boots Riley's initial foray into moviemaking, is clearly a project that he's been sitting with for some time. There are details embedded in the story and the production that can provide the careful observer a lot of joy and it's part of what makes the combination alternate reality/urban comedy/morality play a success. The message of the film is both deeply embedded and often parodied at the same time, which brings another arcing theme to the forefront: No matter how crazy things get, you gotta go to work.

The dual message from the very beginning is that capitalism clearly isn't working for a lot of people and the amount of lying that people often have to do in order to participate in that system is ridiculous. We see this from the opening scene, when Cassius Green (Lakeith Stanfield) tries to present a trophy and a plaque indicating what a great employee he was at former jobs that he never had. The joke, however, is on him, because the telemarketing firm he's applying to will hire any warm body off the street. Once he grasps the basic concept of continuing with the Big Lie by adopting his "white voice" to be a successful caller (hearkening back to Dave Chappelle's assertion that "Every Black American is bilingual. We speak street vernacular and we speak job interview."), Cassius begins to climb the socioeconomic ladder at the office, to the point where he's elevated to the level of Power Caller; a title that fairly drips with the multiple meanings of those in society with money being not only able to exercise the greater freedoms that it creates, but having access to the knowledge of how modern society is even uglier than many people imagine. At that point, he has a choice to make: abandon his social ties and the basic morality of standing up for the majority or continue on the path of societally-determined success (i.e. wealth.)

Along the way, Riley continues to present situations and characters that ask a variety of extremely overt and very subtle questions about the state of society and how many lies everyone has to willingly participate in to keep it moving (Gotta go to work...) These range from the most popular show on TV, "I Got the Shit Kicked Out of Me" being displayed as "I Got the S@!# Kicked Out of Me", presenting the fiction that profanity isn't actually in use, to the very basic idea that the only measure of success in modern America is making enough money so that no one else can tell you what to do (reminding one of Office Space's Peter Gibbons' perfect job: "I would do... nothing.") The screenplay is smart enough to take those subtle jabs like the barely concealed profanity and elevate it to something more elaborate. In that case, it would be Mr. _____ (Omari Hardwick), as the guide for Cassius once he makes the coveted level of Power Caller. Mr. _____ is the only other non-white person in the room; thus, his name can't be spoken, as an example of something that is too profane to be revealed, since he serves the overlords (like WorryFree CEO, Steve Lift (Armie Hammer)) both adeptly and very willingly.

But there are a number of smaller creative details that also appear, from the fun with names (Cassius "Cash" Green, Diana DeBauchery) to Danny Glover tossing in his trademark line from 20 years of Lethal Weapon pictures ("I'm too old for this shit.") Riley also gives us comedic bits that demonstrate the characters' awareness of the bizarre reality and falsehoods that they're all living through, such as Anderson (Robert Longstreet) becoming very disturbed about how DeBauchery and Johnny (Michael X. Sommers) are regurgitating the sales/capitalist message that they've absorbed a bit too well to an office full of employees that will be repelled by it; or Cassius easily entering the VIP room at the bar, using the password that never changes and discovering that he's just one more obstacle to be walked over in a room full of regular people aspiring to a higher status, just like he is.

There were some great production approaches. Depicting the world of the telemarketer dropping into the room where their target is answering the phone was a slick depiction of the age of social media, which often brings the realities of those we're interacting with into our most intimate spaces. The setting of Oakland, a city long known for its working resistance to the social order, but now undergoing a rapid course of gentrification, was a great choice. The contrast between Cassius' one room garage apartment, filled with the poorly lit detritus of being lived in, and the starkly white, museum-like apartment with its view of the Oakland city center, was well done. Lift's quip about the "high production values" of the Claymation movie that introduced his Equisapiens program was also a nice study in contrasts; the use of a medium from childhood TV specials introducing a project of grotesquerie maintained the comedic element of this film and made imagining that kind of delivery a feasible choice, even in our own (slightly) more sane world.

Stanfield did an excellent job in the starring role; so much so that certain scenes attempting to depict his struggle with his new life choices seemed superfluous. We didn't need a couple minutes of him explaining how torn he was when that was already splattered across his face every time he faced the camera. This actually contributed to a bit of a slow period in the middle of the film where I found myself almost doing the "hurry up and move on" wave. We don't really need a lengthy conversation between Cassius and Detroit (Tessa Thompson) to know that the former isn't quite on the same awareness page as the latter. Indeed, Thompson's role was kind of disappointing, in that her artistic depiction of what was happening on the streets didn't add a whole lot to the overall story. Similarly, Squeeze (Steven Yeun), as the labor organizer in the office, was kind of pro forma. Yes, Cassius needed someone new to show him the realities of labor-management action and politics, but Squeeze didn't serve much purpose other than to provide the rather obvious romantic complication.

And that's my one real complaint with the film: the messages occasionally felt too obvious and shaped to provide an easy transition between the second and third acts. We didn't need to be hit over the head quite so hard (with a cola can or not) with the impact of these changes on Cassius. Similarly, we didn't really need the happy ending where he ended up getting the girl (back.) Thankfully, there is a little moment at the end that brings the air of bleakness and the bizarre back to something that was edging toward the formulaic, but I think Riley could have gone even farther in keeping things on the fringes of sanity and still gotten the positive audience reaction that studios lust after.

Regardless, it's definitely a worthwhile film that occasionally hits one squarely between the eyes when considering modern America and its, uh, excesses of all kinds. As Riley noted in an interview, the current political situation made some parts of the script a bit too "on the nose". Something to think about when we all head back to work...

Sunday, April 29, 2018

Past the terrible twos, Badlands kinda grows up

I'm a week behind on Into the Badlands, since season 3 began last week and we're a few hours from episode 2 hitting the screen. Episode 1 of the new season was your standard re-start, laying out the storylines: Widow and Moon's efforts to solidify control of the Badlands; Tilda and the Iron Rabbits being the ultimate outsiders, even to the people they're trying to help; Sunny trying to keep Henry alive even while discovering he's infected with The Gift; and the arrival of The Pilgrim. And, oh, yeah. MK, Prince of Angst, is still around, too.

From a general perspective, I appreciate the fact that they've maintained the wider world introduced last season. Even in a post-apocalyptic scenario, there's still a lot of land and a lot of surviving people out there. In that vein, I appreciate that they've taken care to demonstrate that the natural societal outgrowths and reactions are still present, even in a much-transformed society. The baronial war between The Widow and Chau is displacing, injuring, and orphaning a lot of people. Showing Lydia turning the former isolationist/pacifist religion into a refugee center is a smart turn in that respect. It's a demonstration of the fact that the writers have a larger vision, such that even when society has broken down from our perspective and then breaks down again with the world that is the Badlands, people will still try to band together and recreate the structures necessary to get it moving again.

The arrival of The Pilgrim introduces another of my favorite societal manifestations: religion. While it's possible to see MK's experiences at the monastery as a manifestation of religion, it's also possible to interpret that as a philosophical institution. While traditional kung fu monasteries in film that practice both control and exploitation of their arts have a grounding in Buddhism, my perspective on Buddhism has always been one of philosophy, rather than religion. Religion is a belief in a higher power. Buddhism is a belief in a higher state of being from within oneself. There's no debate about The Pilgrim in this case, however, as he simply announces himself as a "messiah" when his two acolytes use their Gift to slaughter one of Chau's border outposts. Fanatical devotion dropped into a world of opportunists (like Bajie) and cynical politics (the barony system) is always a good springboard. The meta question beyond that is: Now that The Pilgrim is exploiting the breach in the wall around the Badlands, I wonder if we'll see any further explanation for how that wall was built, why it was built, and what's so important inside the Badlands that needed to be protected? Is it just the Widow's oil or something more?

Speaking of The Gift, that angle is starting to lose its luster. At first, we had an instance that seemed like it was unique: MK was a potential threat all by himself. Then we discover that there's a whole monastery of people who've trained themselves to restrain it and are actively pursuing those few who also possess it. Now, we know that not only has The Pilgrim recruited at least two people to serve him that are Gifted, but... sigh... baby Henry is also Gifted, because why wouldn't the son of Han and Leia become the greatest user of the dark side of the Force? Coincidence? No. Henry already carries emotional importance to Sunny, who's a killer trying to protect an infant in a dangerous world (Lone Wolf and Cub, FTW), and to the audience, many of whom will naturally gravitate toward a child and the story connection leading back to the tragedy of Veil from the last two seasons. Did we really need the magic powers to be part of that storyline, too?

Speaking of Bajie, while we're on the somewhat negative side of things, do we really need this kind of "troublemaker" character here? Isn't there enough trouble already? The writers have constructed a pretty ruthless world and yet this self-interested con man has somehow escaped being impaled all this time, despite constantly being captured or enslaved in one fashion or another? Sonny has shown that he's willing to chase down a teenager and execute him for daring to try to hunt him down. After all the contemptible shit that Bajie has pulled, both last season and in this very episode, you're telling me that Sonny wouldn't have just eviscerated him by now? I get that he's one of the gateways to actual knowledge about the wider world, even as he decries the mystical city of Azra for not responding to his radio signal at the end of last season, but that screams "device" to me. He's a bridge out of tedious exposition for the writers, since he can conveniently fill in gaps in the other characters' knowledge while also serving to create new subplots because his deviousness and desire to cheat the system are simply uncontrollable. It's a facade and it's an annoying one; usually cloaked in some kind of comedic trappings, but neither Nick Frost nor the writers have apparently figured out how to do comedy in this dangerous world, so it comes off more as something that needs to be endured, rather than enjoyed.

On the acting front, I think Emily Beecham is growing into her role as the Widow, as there were far fewer "Camera closeup because I'm a badass" moments. But certain idiosyncrasies, like continually preaching her vision of a "better world" while continuing to farm poppies to make money to create that better world are disconcerting. We all have our crutches and if this is the way the writers are working her "end justifies the means" angle in the broad view, I'm OK with it. It's just one of those things that kind of makes you stop and scratch your head when she goes off on a tirade about being different from the other barons. Similarly, there's nothing as jarring for me in the whole series than watching her fighting in ridiculously spiked heels. Yes, they're already doing fantastic feats and there are psychic powers (MK and others) involved, so suspension of disbelief is already a thing. But nothing breaks that suspension more easily for me than watching an accomplished martial artist engage in combat wearing high heels. It's just ridiculous. No one with any choice to make whatsoever would subject themselves to that. Most martial arts are about balance. The arts displayed in Badlands, while fanciful, also involve feats of body control and balance. Both of those are made more difficult while being forced forward onto your toes.

Nathaniel Moon's return is welcome, since Sherman Augustus is an actor with some gravitas and the complexity of his character creates some interesting possibilities. Similarly, Tilda's Iron Rabbits angle has depth. She's trying to make up for the depredations of her mother, but at the same time gets rejected by those she's nominally helping because of the attention she might bring. There's a tenuous dividing line between doing things because they're right and doing them because you're seeking revenge. The two overlap frequently and I think building that kind of inner conflict in Tilda that manifests in how others treat her is a smart turn for a character that could easily have been lost among the other more prominent storylines.

The contrast to that is MK. While I've never been a particular fan of the character and his surrounding story, since it reminds me way too much of a River Tam thing, a la Firefly (the incredible power within this one person in the whole world (or galaxy) might destroy it!), the turn it took last season really only made it worse. Now we not only know that the Gift is about as common as red hair, removing any kind of suspense or trepidation about its presence, but MK doesn't even have the Gift anymore, so he's free to sulk not only about being the prize prisoner of the Widow, but also about the fact that he's not even worth it any longer. That's a recipe for teenage angst if I've ever seen one and the character plays right into it. I'm not sure why recent writers, especially for AMC shows, seem to think that young people being involved in their shows simply demands a healthy dose of teenage pouting about everything that's going wrong in their lives (see: Carl in The Walking Dead for its first 4 or 5 seasons.) I mean, sure, we've all been there as teenagers and many of us even live with some that do the same thing on a regular basis, but this is the one aspect of realism for characters that I could probably do without. At this point, in Badlands, it qualifies as an annoying distraction taking us away from the far more interesting people doing things elsewhere.

I started watching Badlands in kind of morbidly curious "How are they going to make this work?" manner and I'm still kind of there. I'm not compelled to sit down in front of the TV every Sunday in the same I am Game of Thrones or Better Call Saul. But I am interested in some of the directions they're moving (Pilgrim, Tilda), so I think I'm going to keep up with it on an episode-by-episode basis, especially once I move at least some of this writing over to a new site in the next couple weeks. So, stay tuned and all that.

Sunday, February 25, 2018

Aiming high

Let me state up front that Black Panther is one of the better Marvel movies that I've seen. The fact that a movie about a black, non-American superhero put not only non-American culture but the identity of the person in question, front and center of the film, is something that can only be appreciated; as opposed to a film like Amistad, in which a story about the plight of black people presents two white guys as the lead figures in said story. At every stage, not only were black characters able and empowered to make their own choices, but the two prominent white characters (Andy Serkis as Ulysses Klaue and Martin Freeman as Everett Ross) were clearly the (ahem) Tolkien white guys of the film (Gollum and Bilbo Baggins, respectively in Peter Jackson's Lord of the Rings and Hobbit trilogies.) Similarly, all of the female characters were strong, active, and extremely influential in the plot and the progression of it through the film. I have to single out Danai Gurira as Okoye and Letitia Wright as Shuri for being two of the most entertaining characters and whom I would have gladly seen more of. The third in that category would be Michael B. Jordan as Erik "Killmonger" Stevens. I hope that those of you that are fans of The Wire from back in the day are as appreciative as I am that Wallace is still getting screen time and that he has remained every bit as magnetic a presence on camera as he was as a teenaged drug dealer on the streets of Baltimore. Chadwick Boseman does fine as T'Challa, but those three also steal every scene that they're in.

Those are a lot of the upsides of the film. The downsides are a little more nebulous and have a lot more to do with what the film didn't do, as opposed to what it did. A quarter of the way in, Tricia leaned over to me and said: "It's basically a Disney film." Let's put aside the fact that Marvel is now a subsidiary of Disney so, in fact, it actually is a Disney film. We had reached the part where T'Challa was undergoing the ritual challenge for the throne and the festive, musical, colorful presentation of what was intended to be a fairly solemn ceremony (most battles to the death typically are) and it did have quite the Lion King feel to it. Upon T'Challa's defeat of M'Baku to confirm his hold on the throne, the rest of the attendees breaking out in a rendition of Hakuna Matata wouldn't have been overly out of place. ("No more worries... now that you're king.")

And that's kind of the root of my mild dissatisfaction. There were so many intelligent themes in the questions of Wakanda's place in the world and its use of technology that it seemed a shame that the film boiled down to the usual Marvel CGI slamfest at the end where people were blown up and run over by cyber-rhinos (but always without killing them, of course.) This is a question of science fiction that goes back at least to the days of Star Trek and the Federation's prime directive. Despite having the power to positively influence the lives of billions of people, and especially those of black people, across the globe, the rulers of Wakanda have always been more concerned about the destruction that vibranium could cause if it was misused or acquired (read: conquered, colonized, stolen, etc.) by those with a less restrained outlook on the world, at large. This is just another take on the justifiably discarded "noble savage" canard of fiction (especially fantasy and SF over the years), where the innate goodness of those people uncorrupted by civilization is taken as a given. Despite Wakanda's extremely advanced civilization, their reluctance to engage the rest of the world on open terms is presented as a safeguard for that world. The unspoken fear is that if they did choose to engage, the power locked in the tiny nation would quickly become more bane than good. Even in the case of obviously self-interested and ambitious characters like M'Baku, it's assumed that his noble understanding of the power of vibranium would prevent him trying to take the throne with outside assistance or threatening the tribal council with the revelation of their secret in order to get what he wants.

The big question, of course, is why these questions weren't being asked in the intervening years of colonial domination, slavery, racial injustice, and persistent poverty. Clearly, at least some of the population was dissatisfied enough to be regularly engaging in efforts against human trafficking (Nakia, played by Lupita Nyongo'o) outside the borders of Wakanda. Equally obvious was the ruling government's concern over the state of people in other nations, since they created the War Dog program to enable assistance to those peoples. Of course, "War Dog" is a strange name for a program that's supposed to be helping people progress out of poverty or enslavement and it begs the question as to why more overt efforts hadn't emerged during the previous two centuries of oppression. One can fall back on the dominance of tradition over sanity which tends to disrupt all kinds of cultural progression (American reverence for a colored cloth, anyone?) and which you can make a plausible story argument for in the case of a nation with overnight spine repair tech and laser weaponry that still decides the transition of a hereditary monarchy through ritual combat.

Similarly, the film has a bit of a Batman problem in that the title hero is not nearly as interesting as his adversaries. Killmonger was a fascinating villain because he was motivated not only by personal vengeance, but a relatively sound and understandable political agenda. You could have given him far more screen time because every moment that he was on screen was fascinating. And yet, in the course of one film, he's already gone. Now, this is the superhero genre, notorious for its inability to let any character rest in peace if someone has a new (using the term loosely) idea. But no writer should want to cheapen the legacy of Jordan's performance and Killmonger's character in this first film by bringing him back in the "bad guy turned good" routine. There was a lot more to say about and with him here, in this film, right now.

This is an example of it being obvious where the cuts were made. Clearly, there should have been more to Killmonger than just being the "real" threat where Klaue was the opener. But there's only so much one can cram into a 120 minute film. For example, you can't tell me that people with that much technology and innovation wouldn't have figured out how to preserve the heart-shaped herb so that they weren't forced to maintain a ritual garden. That dramatic moment where Killmonger burns it fell flat simply because of questions about how they could have let this happen. This wasn't a formula that they've stumbled upon that works once like Steve Rogers. This was thousands of years in development and maintenance. You're telling me that in that whole time, no one has developed a way to keep that tiny garden from being threatened by someone dropping a candle? Some of this stuff could have been given room to breathe with the space provided by, say, a 10 episode Netflix series. But in a film like this, you only have time for a couple good ideas before the last third of it has to be taken up with the CGI extravaganza. The best superhero stories I ever read had very few, if any, explosions. But sometimes you gotta feed your expected audience so, there it is.

I liked a lot of the other little touches in the film, like Idrissa Soumaoro's music showing up as T'Challa and other characters stroll around their homeland. I originally mistook it for Issa Bagayogo, another Malian artist, but was pleased to know that I wasn't off when it felt like the writers and producers had taken particular pains to make this an African superhero story and not just a story about an American who is somehow king of a stereotypical nation in Africa. Credit, of course, is due to Stan Lee and Jack Kirby for being willing to step outside the (ahem) clearly drawn racial lines of superheroes at the time and to create a black character who was not only a superhero, but also the king of an entire nation in his "civilian" life. You can't get much more empowered than that, especially since he was able to leave the throne to someone else's stewardship and run around with the Avengers for years. Among the other touches was the presence of multiple African languages and different ones for different sections of the country (whereas most Wakandans spoke Xhosa, the Jabari, in the mountains, spoke Igbo.) That's an example of a production team that cares about its product (and, of course, doesn't want to suffer the wrath of the Internets.)

So, yes, it's still a superhero film that drags a bit in the middle and blows up half the terrain at the end. However, it's also a superhero film that asks a number of interesting questions (unlike, say, Guardians of the Galaxy), albeit not thoroughly, and presents a number of great characters that I'd love to see in future releases.

Thursday, January 4, 2018

For my people are foolish; they know me not

"They are stupid children and have no understanding. They are shrewd to do evil. But to do good, they do not know." - Jeremiah, 4:22

Simone got a student subscription to Spotify, which came with a Hulu subscription. (Media consolidation. Yay?) I'd held back on getting one because there's so much to watch on things we're already subscribed to (Netflix, Amazon, HBO; we also watch Vikings and Top Chef on "regular" TV) and I didn't feel like paying for yet another service. But I was interested to have it dropped in our laps for "free" because I had wanted to see The Handmaid's Tale. I'm a fan of both Margaret Atwood's novel and the 1990 film with Natasha Richardson and Robert Duvall. I'm also a fan of Elizabeth Moss, as while Peggy was not always among my favorite characters on Mad Men, she was always one of the more grounded and realistic and, thus, interesting ("Why are you using your sexy voice?") people in the series. I have an attachment to characters that are placed in extraordinary circumstances and get played in the same manner that you or I or people we actually know would react. In the series, Offred is like that.

It's a departure from the two previous tellings of the tale, but I think an appropriate one. 2017 is a different world for women than 1985 (book) or 1990 (film), although regrettably not that different (#metoo.) The gloomy, ethereal Offred that appears in her journal as represented in the book or the timid and cowed stance that Richardson played in the film, while certainly possible, wouldn't be quite as believable as the more confrontational and outraged approach that Moss has taken. She's still largely keeping herself within the boundaries as set forth, as the idiots have the power at the moment (MAGA!), but she's pushing back occasionally (we're only to episode three) and constantly fuming to the camera when alone.

Similarly, the "ceremony" in the TV series is a much different atmosphere than it was in the film. In the latter, the event was emotionally traumatic for Richardson and Faye Dunaway as Serena Joy. In the series, Moss has gone for the psychological protection of simply checking out while it happens and the only one emotionally impacted seems to be Serena (Yvonne Strahovski.) I think some of that is the difference between a film and an ongoing series. In the film, you have a discrete number of times that you're going to be able to impact the audience with the shock of the event, so it's played to that impact. In the series, this is a regular thing, both within the story and the structure of the series, so either you have to play it up as an event of outrage at every opportunity, which would likely get Offred sent back to the Red Center and the audience tuning out after the fourth or fifth time, or you have to show that it's something that she's adapted to as best she can, so the audience can adapt to it, as well, without questioning why she hasn't committed suicide or taken some other action of finality or escape.

Production design was another series of contrasts that I noticed. The book never really gives a timeframe for events and neither does the film, but the situation has clearly been present for some time. Although the Red Center in the film is clearly a former high school (the sleeping chamber for the handmaids being a former gymnasium), everything is very clean and formal. Furthermore, the Guardians of the Faith all have detailed uniforms. The series, OTOH, is specific about the fact that the transformation from the United States to the Republic of Gilead has happened within the last few years. The Guardians all wear black clothing, but not a standard uniform (a variety of jackets, knit caps instead of berets, etc.) and the Red Center is depicted as a school, but one with peeling paint and dirty windows; clearly an ad hoc operation taking place in a school that was no longer needed with the reduced number of children. Despite the series having a significantly greater budget than the film, an attempt was made to make things appear less shiny for the sake of the story and it was clear that the Gilead system was still being put into place. I always appreciate that level of care. Also, the series takes pains to return to some of the particular detail that Atwood provided in the novel. The film showed the handmaids in red headscarves and fairly form-fitting dresses. They were still objects of attraction. In the series, they're in loose gowns that hide their bodies and they wear the large bonnets that prevent anyone not directly conversing with them from seeing their faces. They've also been careful to keep the actresses playing them as plain as possible. These are women that are not intended to be objects of attraction, but simply objects; possessions; tools of the state and the god that looks over it.

On the acting front aside from Moss, it was interesting to see Joseph Fiennes as the Commander, although we haven't seen that much of him yet. It's a fairly reserved role compared to the things he usually plays. I was pleased to see Samira Wiley as Moira, since she was a favorite from Orange is the New Black. She and June's former husband, Luke (O. T. Fagbenle) were also the first indication that the series producers had decided to do away with the "children of Ham" theme from the previous versions, which drew clear racial barriers, in addition to gender, sexuality, and ethics. As many others have noted, Ann Dowd as Aunt Lydia has been a particular highlight, although I have to say that I loved Victoria Tennant in that role in the film.